Communicating in Real Time, Near Time, and Far Time

Behind the scenes here at Lucid Meetings, we talk a lot about how to support organizations as they work to establish a robust, effective, and resilient communication architecture.

- Communication Architecture

- The method and frequency by which information, attention, and intent flows between people, teams, and systems in your organization.

See also Meeting Flow Models and Meeting Operating Systems.

Today, I’m inviting you to “think out loud” with us as we work to refine these ideas.

To develop an effective communication architecture, you need to understand what your teams need to communicate and when this communication needs to occur.

We believe that it’s useful to draw upon a handful of mental models, or metaphors, when attempting this work. Metaphors create a bridge between the simpler, criteria-based decisions (such as whether to adopt Slack or Teams) and the more important, complex decisions (such as how/if to share financials with employees).

Metaphors give us language that helps make complex issues relatable.

Here’s an example.

Imagine that the communication flowing through your system is like water flowing through the natural world. With regular, refreshing “rains” of communication, some parts of your organization might be flourishing. Others, cut off from feedback and new ideas, dry up and wither. Finally, some groups refuse to communicate, hoarding their information in stagnant little pools where it begins to fester and stink.

Visualizing the information-attention-intent communication energy in your organization as akin to the energy in a natural system like the water cycle can give you and your team a metaphorical model to use as you work to better channel that energy.

For instance, instead of asking whether a team is dealing with too much information, you might ask if they’re being flooded. Then you can consider not only the volume of information the team consumes, but also the timing and means of delivery, which opens up new ways to route that information so it doesn’t flood in all at once.

Most folks can relate to the energy metaphors and find those useful. Do you? Let me know. I’d love to learn how this resonates for you.

We haven’t been as successful, though, when trying to communicate concepts related to time. Thinking out in time is one of the more challenging things to do, because as a species, we come laden with a host of biases, blind spots, and counterintuitive quirks that get in our way.

For extra fun, check out the recency effect, the end of history illusion, and the “uh-oh” effect.

Thus far, we’ve tried to help folks get their heads around designing for time by using the same tired metaphors you’ve probably heard before.

We’ve tried visualizing our organization on a journey, where the kind of communication we need when planning our trip isn’t the same as it would be when we’re lost half-way to our destination. This metaphor works OK when you’re mapping out communications for an individual project, which has a defined start and end, but it’s inadequate for thinking through communications for ongoing work.

We’ve also used personification, imagining our organization as a person going through different life stages.

This metaphor lets you consider how the kind of “architecture” we need as a young adult in our first apartment isn’t at all ideal when we’re in our sandwich years, supporting multiple generations under one roof. This metaphor is kind of useful, but it’s also so big and abstract and so mysteriously unknowable (like, how can we possibly predict what an adolescent organization will be like when it “matures”?) that the metaphor becomes more of a thought exercise than a useful tool.

It’s important to overcome the challenges inherent in talking about time, though, because we must consider a group’s communication needs over time to create an effective communication architecture.

A Story in Real Time, Near Time, and Far Time

For every communication that occurs, we have three potential audiences:

- The people directly involved and communicating. That’s the Real Time audience.

- The people who put the information that came out of the real-time communication right to work. That’s the Near Time audience.

- The people who look back to that information for moments of significance. That’s the Far Time audience.

For example, if you’re working to run great business meetings, it’s not enough to think about what happens during the meeting in the Real Time communication. You must also ensure that meeting results make it out to the Near Time and Far Time audiences too, because if you don’t, your team either has to invite everyone to every meeting, or you’ll find yourselves repeating the same conversations with each audience.

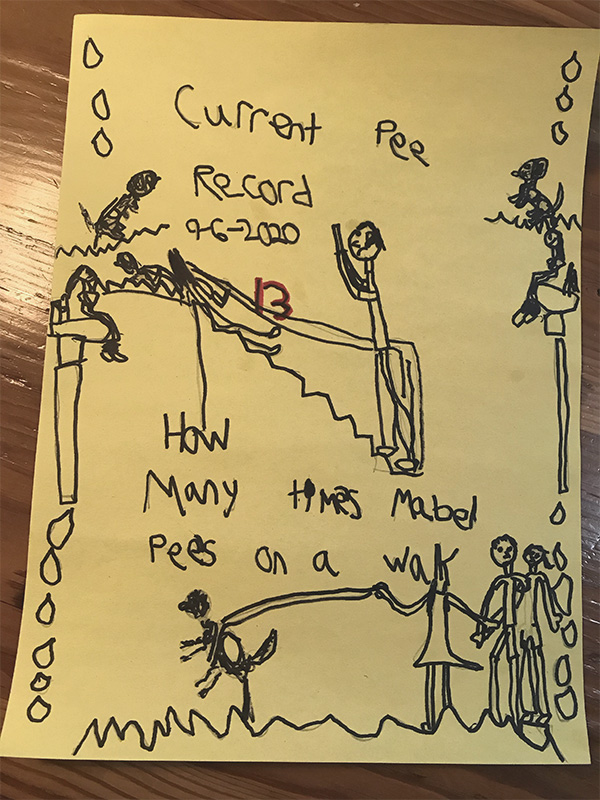

This weekend, my daughter gave us a good illustration of the kind of mistake you might make when you’re not clear about how to best communicate over time. Hopefully this story will make this idea bit more relatable. It’s simple and a little gross, which should also make it easier to remember. Let me know in the comments what you think.

This is my dog Mabel.

She’s a working dog, bred to hunt truffles. This means she likes to sniff things. She likes to sniff things a lot. As a sniffing type of dog, she spends much of our walks about the neighborhood “reading the mail” left by the other neighborhood dogs, then depositing her damp little replies.

Mabel’s no dummy. She knows we’ll pause and wait if she needs to pee, which will give her more time to sniff. As we walk along, she’ll stop to pee 5 or 6 times each mile. We often think she’s faking it.

This Sunday, Mabel took her sniff-dribble-sniff routine to a new level. My husband, daughter, and I walked 1.5 miles to the farmer’s market and back, which we do most Sundays. Mabel stopped and peed and stopped and peed, until my husband started keeping count. At 10, we were all amazed at her bladder capacity. By the time we reached home, she’d left piddle notes for the neighbors 13 times. 13 times!

It was a new record.

“Wow, Mom. A new record! I wish I brought my camera,” my daughter declared.

Now, that would have been a mistake. It’s similar to the mistake business folks make when they record a meeting and figure that anyone who wasn’t there will watch the recording. Ha! As if.

Happily, my daughter’s no dummy either. She thought about taking pictures for a minute, and realized that when we looked at the pictures later, there wouldn’t be any way to tell why she’d taken a picture of Mabel peeing. It’s not like you can see why that one pee pic was special without capturing all 13 together, and by the time we realized we were witnessing a history-making marking session, the first 9 were in the past.

In Real Time, we communicated our observations about Mabel’s feats and created a result; the new record.

When we got home, we shared the story with our son, giving him a Near Time summary of the highlights. Now he knows to keep track when he takes Mabel for a walk, just in case she breaks the record.

Finally, we agreed that we need some way to mark this achievement for the future. Right now, it’s fresh in our memories, but give us a month and we won’t remember to count. I don’t know what our future selves will be preoccupied with, but I’m pretty sure it won’t be dog piddles unless we do something now to communicate the record and keep it in front of our Far Time selves. Which of course we have to do, because really, what good is it to have a record-breaking event if you never try to improve upon that record?

I’ve invited my daughter to design a chart we can use going forward. School’s started, so I’m hoping her 3rd grade teacher gives her credit for this science/art/math project.

And, I’m hoping the record stands for a good long time, because stopping 13 times in one short walk is really annoying!

To sum up, here’s how the communication flows through this story across the three time scales.

- Real Time: We’re actively walking, counting, and making sense of what we’re seeing. We have all of the information. With it, we create a new thing – the piddle record!

- Near Time: We share a story about the walk and the new record with our immediate family, so they can know to keep count going forward. We communicate the highlights, and enough context to quickly give everyone a feel for the event. The hour-long Real Time communication is condensed for use by the Near Time audience.

- Far Time: we post the key result (the record) in an obvious way so it can be found and built upon in the future. People who weren’t even around this weekend will be able to see this and help us keep track in the future. Two, three years from now, we’ll pull out a binder of 2020 memories and this record will be there for us to relive in Far Time.

| Energy | Real Time | Near Time | Far Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information | Comprehensive

We work to:

|

Summary

We work to:

|

Signifiers

We work to:

|

| Attention | Full, Commanded | Selective | Nominal |

| Intent | Start, Commit | Learn, Do | Remind, Improve |

Putting this Idea to Work

With this in mind, consider communication throughout your organization. What do you need to create and share in Real Time? What needs to be summarized for use by others in Near Time? And how can you mark those ideas truly worth remembering for the organization you’ll become in Far Time?

Or in other words, when are you counting piddles, vs informing others to count the piddles, vs celebrating the all-time high piddle record?

Consider also your communication methods.

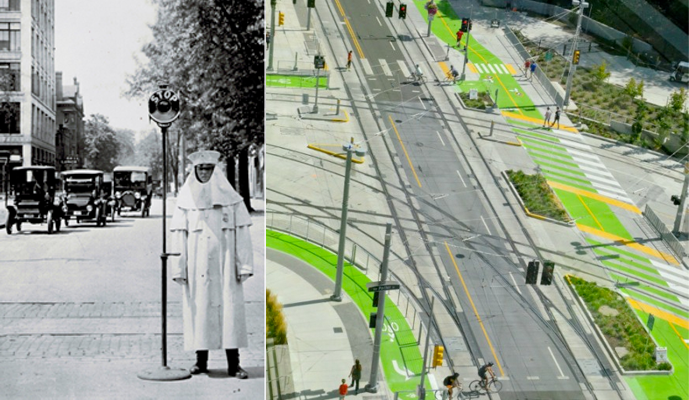

You’ll often see terms like synchronous or asynchronous used to describe different ways of communicating. Meetings are typically considered synchronous, since most folks discount the value of all the communication that happens before or after. Chat and workstream applications are often described as asynchronous, even though many people expect instant replies to any message they post.

In reality, most communication methods can work across multiple time scales. As you improve your organization’s communication architecture, consider what the expectations and agreements should be for each communication method.

For example, if everyone believes meetings are only Real Time, meaning you don’t expect anyone to share information in advance or send out results afterward, then you won’t be able to rely on meetings for making decisions that stick or creating accountability. Alternatively, if you set expectations that reports will be distributed in advance and records kept, you’ve unlocked meeting value across multiple audiences over time, and improved your system’s ability to harness that energy.

At least, that’s how I hope you’d use this idea. Now you tell me – is this useful? What else is coming to mind for you now, and how would you improve on these beginnings? Get in touch and let me know.