5 Steps to Improving Engagement in Meetings

Note: This post is an excerpt from Chapter 8 in Where the Action Is: the Meetings That Make or Break Your Organization, available now on Amazon.com.

Participation propels perceived meeting quality. We call it participation when we are attending a meeting—as in, “I had a chance to participate.” Meeting leaders often use the term engagement to describe the same thing.

The Spectrum of Meeting Engagement

Engagement is about getting the individual into the meeting, about breaking through the noise and fog of whatever may be going on for each person so they can focus their will on the collective goals. Meeting engagement is observable behavior; you can see whether or not someone engages in a meeting. This engagement falls across a spectrum of behavior that looks something like this.

At the bottom end of the spectrum, you have the Disruptive behavior— things like:

- Arriving late or not at all, or leaving early

- Side conversations

- Interrupting

- Complaining

- Excessive negativity and personal attacks

Next, you have the inattentive people: these are the folks checking email or doing other work in the meeting, the multitaskers, the people who are spacing out, and those who nod off.

Then, we start getting into the range of acceptable behavior with people who are paying attention—actively listening and perhaps taking personal notes.

The tricky thing is that it’s very hard to tell the difference between someone who is actively listening and the person who’s looking at you but thinking about something totally different. From the outside, there’s no telling.

This is why we look for people who are actively participating in meetings. A person participating is answering questions when asked, talking with other participants, and following instructions. It’s a reactive way to engage rather than proactive, but it’s also obvious to see that this person is truly in the meeting.

Moving past participation, we come to those who are contributing by helping to shape the meeting outcome. People presenting reports, offering ideas, and raising questions are working to improve the meeting results.

Finally, at the highest level of engagement, you get the people taking ownership for the meeting result. This includes the meeting leader for sure and also anyone who’s really driving a decision or setting the topic. Those folks are invested.

But meeting engagement can come in many forms. Someone who offers to take notes is engaged, but so is the person who loudly bullies everyone else into submission. One provides productive, generative energy to the group; the other destructive energy.

Generative energy drives forward momentum. Destructive energy kills it. In the middle, we get inertia, which we all know from our basic physics lessons devolves into entropy. A body at rest stays at rest.

Embracing core competencies, like defining the meeting purpose up front, and the use of an effective meeting structure work to encourage meeting engagement and productive energy. Beyond these basics, there are five key steps meeting designers can follow to increase meeting engagement.

The Five Steps to Improving Engagement in Meetings

- Define what you want people to contribute.

- Ask for engagement.

- Make space for people to engage.

- Acknowledge contributions.

- Use what you receive.

1. Define What You Want People to Contribute

The first step is to clarify what kind of engagement you want to see. What do you want people to contribute and what will you do with those contributions?

I hear from many leaders who want to “get their teams more engaged” in meetings. When I ask for details, they talk about all the things that they don’t want people to do.

- They don’t want people to show up late.

- They don’t want anyone checking their cell phone or email.

- They don’t want a bunch of side conversations going on.

- They don’t want folks to tune out.

This is a clear picture of disengagement, but the vision for engagement boils down to “paying attention.”

I am always surprised by the number of meeting leaders who come to Lucid Meetings looking for ways to “get their team engaged,” then describe meetings where they have everyone in a room, spend 20 minutes talking at them, and finally ask for input. There is nothing in that approach which tells people that they should expect to provide input before the meeting, and after 20 minutes, there is very little chance that anyone will still be paying attention. A go-around at this point often results in “Nothing to add” from most of the group.

If you define engagement in your meetings as having people simply pay attention, then you’d better plan to be entertaining. Unless your financial reports are chock-full of cinema-worthy drama, I recommend seeking a clearer path to engagement.

Also, do not anticipate that people will rate a meeting highly where they simply paid attention. “Paying attention” does not qualify as “participating” from an attendee’s perspective.

To truly engage in a meeting—beyond just paying attention—people need an active part to play. They need a job to do. These jobs can be simple, like raising a hand to indicate agreement, or helping the group keep track of time. These jobs can also be complex, like they are when participating in a collaborative Workshop or building a complicated decision matrix together.

Too often we assume that people know we want their participation.

To break out of these assumptions, ask yourself:

- What will it look like when someone engages in your meeting? What are they doing?

- Why would someone engage in your meeting? What’s in it for them?

- How could you know that they were engaged?

- After they’ve engaged, then what?

What happens next with whatever they’ve contributed?

The answers will depend on the meeting. You may want people to share any concerns they have about a plan, or ideas for solving a problem. You may want to know what they like about how the group works, and where they’re having a hard time. Perhaps the team needs information, or simply a chance to connect.

To increase participation, each person must have a reason to be there. When you schedule a meeting, only invite people you explicitly expect to actively participate. If you’re inviting someone just because you’re not sure who needs to be involved, or you’re afraid to hurt someone’s feelings, what you’re actually doing is creating the conditions for a bad meeting because those people have no good reason to participate.

2. Ask for Engagement

Once you know how you’d like people to engage, it’s time to ask for that engagement.

The simplest way to engage someone is by asking a question, then waiting for an answer. This works well in a one-on-one dialogue. The structure is:

Question → Answer

In this case, the job you’ve asked of the other person in the meeting is to answer the question. In a group, however, this question → answer structure often falls flat. Just like with any task you throw out to a group, you’re likely to see several people keep quiet as they wait for someone else to answer.

A better structure for groups is:

Question → Go-around

Here, the meeting leader goes around the room and asks each person to answer the question one at a time to ensure all participants contribute. Question → Answer or Question → Go-around are the most straightforward ways to ask for engagement, but not always the most useful or— frankly—the most engaging. After you figure out what kind of engagement you want, you can ask for that specifically. The asking can come at several times and in many forms. These meeting techniques all provide other ways to ask for engagement.

- Meeting pre-work: asking people to complete tasks assigned before the meeting so they can arrive informed and ready to engage. For example, you can ask people to read a report in advance and come prepared with the specific feedback you need.

- Ground rules: these are code-of-conduct rules that the group is asked to respect during the meeting. For example, “turn off cell phones” or “commit to stating objections in the room” are ground rules which ask people to stay in the conversation.

- Activities: participants are asked to complete these together during the meeting.

- Meeting roles: jobs individuals are asked to perform in the meeting.

Finding the right way to ask for engagement is an overwhelming task if you lack clarity about the purpose of the meeting. Once you know why you’re meeting, however, and what you need to accomplish within it, it gets a lot easier to figure out what to ask.

3. Make Space for People to Engage

This step is simple, often neglected, and powerful.

If you ask for engagement, you must make sure there is time for people to give it to you.

The Five Hippopotamus Rule is a simple technique that illustrates this point. After you ask a question, remain silent for at least five seconds (the time it takes to count in your head, “one-hippopotamus, two-hippopotamus,” all the way to five) before speaking again. This gives everyone time to consider your question. The silence also shows them that you really do expect to hear someone else provide an answer.

Too often, leaders will tell a group that they want to hear everyone’s feedback on a new proposal, then spend 90% of the meeting presenting the proposal and leaving only minutes for the Q&A.

To the people invited, this feels like a sham. Clearly, these leaders didn’t actually want input, because if they did, they would have made space for it. Many well-intentioned presenters have insulted and alienated meeting participants by not allowing adequate time for the engagement they asked for.

As you consider the kind of engagement you want (the ask) and work to plan your meeting accordingly, you will find that making time for engagement is a forcing function, often requiring teams to plan meetings involving fewer people or addressing fewer topics. For example, if you ask for feedback on a presentation and give each person only two minutes to talk (which isn’t very long), a group of 10 people will require 20 minutes just to go around the room. Then, you had better anticipate that some of this feedback will lead to further discussion, since differing opinions will warrant clarification, debate, and building upon. Twenty minutes is not a problem if the whole meeting is dedicated to feedback, but it’s a huge time commitment if it comes after a 40-minute presentation.

Making space for engagement in a meeting means that:

A. Each person must have the opportunity to contribute.

One reason you need to be selective with your invitations: research shows that the more people present in a meeting, the less each person participates—or at least, the less most people feel they participate—and the harder it is to keep everyone coordinated. It’s easy for someone to feel that they are not needed (or, worse, like they’re wasting time) whenever the group gets larger than 5 people.

B. Each person can come prepared to contribute.

We all know not everyone feels the need to be prepared—or even informed—before they’ll happily offer up their opinion. But then you’ve got a meeting dominated by people who like to talk, which doesn’t make anyone look good.

So as a meeting leader, you want to make sure participants have any pre-reading or information they need to get prepared beforehand. This means not only do you have to make space during the meeting for engagement but also on the calendar preceding the meeting. Happily, when people come informed and ready, you’ll also get a better result in the end. (Here’s where that agenda comes in handy!)

Engaging meetings will need to include fewer people and/or cover fewer topics, or get blown up into full-on facilitated Workshops. In other words, structuring meetings for engagement will force you to run a tighter ship.

4. Acknowledge Contributions

“Thank you.”

At the very least, people who make a contribution to the meeting deserve thanks.

For many individuals, speaking up in a group means taking a personal risk. Some people are shy, and some environments are hostile. Whether the risk arises from internal or external factors, it still takes courage and effort to overcome. When this contribution is then glossed over, when it’s dismissed, or when you haven’t made time for it, people learn that the risk was not worth the effort. It is not safe to risk making a contribution in a group that does not appreciate that effort.

To encourage more engagement in a group that is still getting used to it, make a point of acknowledging and expressing appreciation for the effort. This makes everyone feel valued, reinforces the behavior change you want to encourage, and increases the likelihood that the team will contribute more going forward.

Visible note taking, the fourth core competency listed in Chapter 5, provides a simple and useful way to acknowledge contributions. When a person adds to the conversation, the note taker records what that person said where everyone can see it. You’ve probably seen facilitators do this in a Workshop when they write down replies on a flipchart. In everyday business meetings, it’s often more useful to write down replies in a shared electronic document that everyone can access.

Visible note taking acknowledges people’s engagement by literally writing it down. It also makes it radically easier to get to step five….

5. Use What You Receive

Finally, to get more engagement in meetings, make sure that the engagement matters to what happens outside the meeting. Engagement for engagement’s sake is a mistake.

A meeting is never the point—it is always a means to an end.

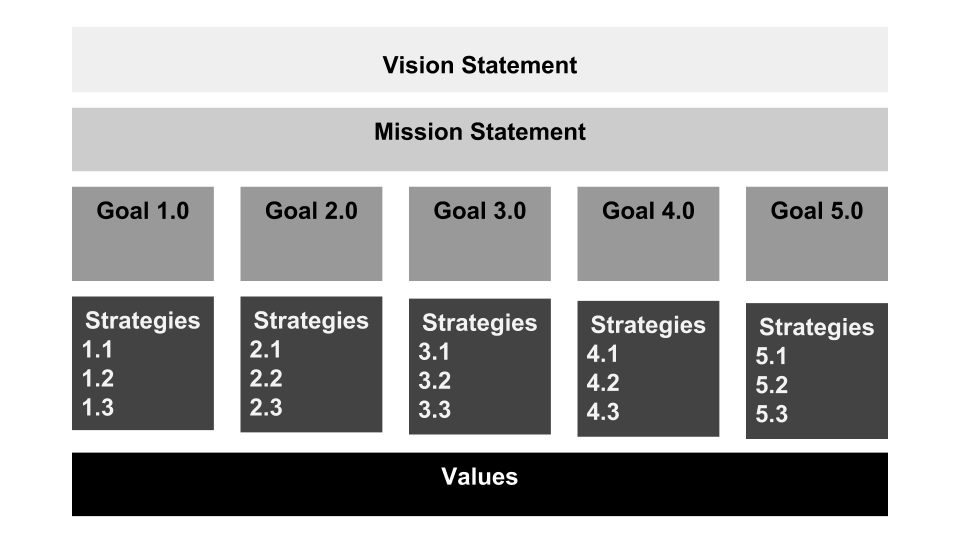

Strategic Planning Workshops are notorious for creating a significant outcome that never gets used, and not because they fail to engage participants. It is possible to run a fabulously engaging Workshop to build out your company’s strategic plan, only to then have that plan sit on the shelf for a year.

If all the exciting thinking you did in the meeting doesn’t actually change what you do when you leave that meeting, it is wasted effort, and everyone involved will know it. Later around the water cooler, your meeting will be derided as a boondoggle.

When it comes to engagement, the rule is use it or lose it.

No one appreciates making a good-faith effort to help a group, just to have this input ignored. It’s disrespectful, patronizing, and a waste of their time.

On the bright side, if you know how you will use the group’s contributions after the meeting (which you do, because defining this contribution is step one), this makes it much easier to figure out what kind of contributions you need. And if you take visible notes during the meeting, everyone can confirm that what you’ve written is what they intended, reducing the chance that you’ll hit resistance later.

Getting clear about why you’re meeting and what you will get at the end—the purpose and desired outcomes—is the most important step in creating a great meeting that not only engages your team but also serves your business.