Designing a Thoughtful Return to the Office

It looks to me like we’ve broken work. Not for everyone, and not everywhere, but for a lot of teams the WE part of work isn’t working.

I know. This isn’t new.

Work has been kinda broken for a lot of people for a long time. But take it from a lady who deploys lots of duct tape and safety pins: there’s a big difference between kinda broken and all-the-way broken.

The lockdowns broke office work. They forced many people out of jobs, and many more into isolation in an attempt to protect our communities. Even though we went through this experience together, we experienced it alone. We were forced to craft a way of working that was uniquely tailored to our individual circumstances. As “3 weeks to flatten the curve” morphed into multiple years with an ever-shifting end goal, we developed new habits.

We forgot how to be with people.

“People are a little nervous and jumpy at All The Socializing. We’re out of practice.

A few people told me later how they had to take People Breaks in their rooms—literally, breaks from too much peopling. (Is peopling a verb? Is now.)”

The amazing Ann Handley, reporting on what it’s like to go to conferences now

Working from home requires less compromise. We don’t have to navigate when to eat, what to wear, traffic, background music, or any of a hundred little things with anyone else. None of these compromises overwhelmed us before, but now that we’re unused to them, each one seems like a much bigger deal.

All that inconvenience can feel worth it when a team comes together and connects. There are some experiences we can only have when we’re physically together, and these experiences are what help us hold on to the strong sense of WE that’s needed to answer the call of the current moment.

Together is Together.

The brokenness of work is creating uncomfortable contradictions.

Facing growing cultural, economic, and climate crises, leaders are calling for more innovation, more unity, and more pulling together to rise above it all.

With rising anxiety, illness, and awareness of inequalities, leaders are also calling for more self-care, more recognition of each individual’s uniqueness, and more allowance for each person to live and work as they will.

It is very hard to prioritize a strong WE and a strong ME at the same time.

Knowing that their company’s WE has become weak, many leaders are calling teams back into the office. They’ve had experiences telling them that when people are together, they become more than the sum of their parts. They miss the camaraderie and interesting ideas that arise when people engage in serendipitous conversation. To rebuild this WE-ness, they compel people back to the office in the name of culture, serendipity, productivity, and other ineffable benefits which they’re sure will emerge if only people would gather.

Microsoft’s recently published workplace trends article calls this productivity paranoia, and their data shows that they’re hearing the same stories we are.

Of course, working from home invites serendipity, too. When my daughter sliced her finger and the dog threw up on the carpet, I was there. I was there when my neighbors needed someone to sign for a package, and I got a free whiskey tasting in return. I caught the ripe figs before the squirrels stole them, and I know so many more Taylor Swift songs than I would have if I had been away in an office.

So when business leaders ask people to spend some days in the office in the name of ‘culture’ or ‘serendipity’ or ‘productivity’, they are pitting the potential benefits of doing the work they’re already doing in the office where they might possibly also have a nifty encounter, against the known benefits of doing the work at home where they can be there for friends, family, relatives, pets, and the rest of the life they’ve settled into during the extended absence.

If you want people to show up more often, make it worth the trip.

– Adam Grant via LinkedIn

He is not talking about free pizza. Perks and bribes aren’t working.

At one company, the director of people and culture stood alone with cake beneath a balloon arch, ready to welcome employees back to the office. No one came.

In others, people went to the office only to find that the rest of the team stayed home – or moved to another town – and they didn’t bother going back.

Mandates aren’t working.

Leaders try mandating some days in the office, then quickly reverse these policies when they can’t find replacements for everyone who quits in protest. Quitting is easier now because as our sense of WE weakens, people no longer see the organization as a key element of their career progression. If they don’t like a policy or if they want to take their work in a new direction, they look for an organization that fits their criteria rather than negotiate those changes where they are.

There’s no good way to reverse the lockdown. It went on for too long and now we’re accustomed to working from anywhere. More importantly, teams have proven that they can get tasks done when working remotely, so they no longer believe there’s a compelling justification for the commute.

So what are we to do?

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function. One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless yet be determined to make them otherwise.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald

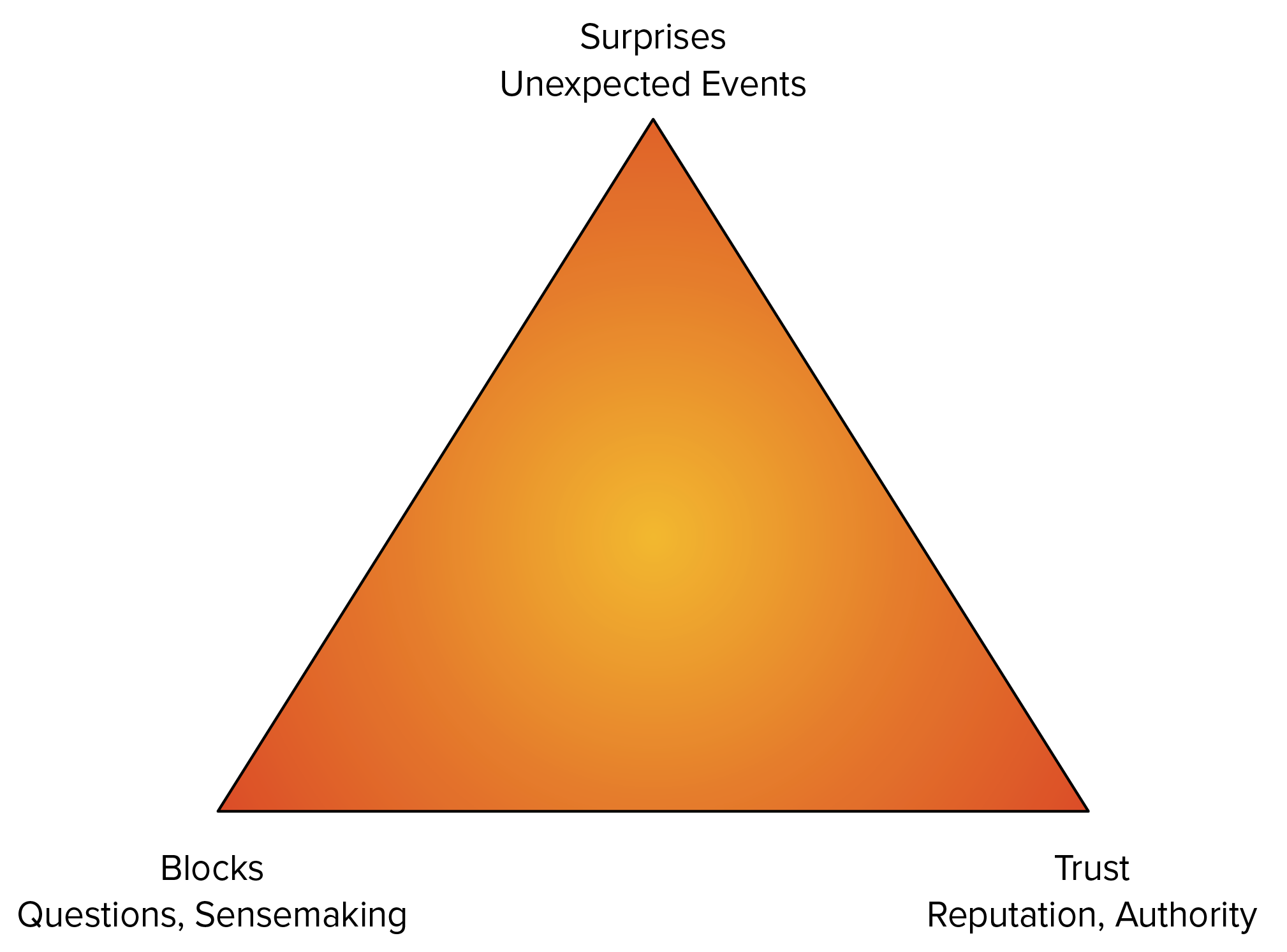

We have two opposing ideas to balance as we decide how work will function going forward.

- ME. Many people benefit when working from home. They use fewer resources, spend more time with family, and have more control over the work conditions that help them focus.

- WE. Many teams work better when together in person. They understand each other more clearly, address small questions more quickly, and create friendships more easily.

To find the right balance, you need to gather and apply some first-rate intelligence.

If you want teams to return to the office, they need to believe that it’s better, cooler, and entirely worth the effort. They need to understand why that journey must be made, both logically and emotionally. They need to experience that being together in the office is better to make that belief stick.

How might you give teams an opportunity to have that experience and form their own beliefs? After talking with leaders about what is and is not working with their returns to the workplace, I suggest this approach.

A Process for Designing Thoughtful Hybrid Work Agreements

I’m a fan of workplace policies that distribute authority broadly and trust people to make responsible decisions. As any good leadership coach will tell you, the only solutions that work are the ones that people find for themselves.

Instead of telling teams how to work, consider establishing a process that teams can use to make those decisions for themselves.

Here’s how that might look.

0. Commit to deciding WITH (not for) teams.

This process will only work if the leadership group commits to operating transparently and fairly with employees. Leaders determine the options, the timeframe, and the framework for communicating decisions.

The teams make the decisions.

Before beginning this process, leadership must commit to honoring these decisions for a pre-defined period of time.

1. Decide on the options and a timeframe.

Every company needs to decide what to do with its office space. No one wants to pay the heating and maintenance bills for large empty offices, so if you’re considering changes to the available office space, make this clear.

Teams need to know what resources they’ll have when they’re together, and how long they can have them. Can they reserve a meeting space? Can they have a desk of their own? Can they leave work in progress up on the walls? Be ready to answer questions like these.

Also, tell teams about any planned gatherings of the whole company, such as monthly all-hands or quarterly retreats. These events interrupt teams’ normal operational cadence, and they may want to schedule their in-person events around them.

Finally, set deadlines. When must teams submit their hybrid work plans? When will the combined plans be finalized? When will these policies be reviewed and revisited?

2. Share WHY teams should consider coming into the office.

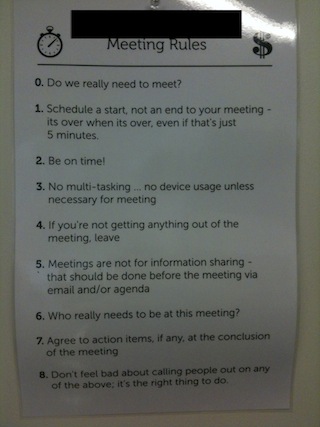

Every team engages in both solo and group work. What kind of group collaboration tends to work better when teams are colocated? What’s the purpose of being in the room together?

It’s important to provide specific examples because the promise of ineffable serendipity isn’t that compelling – especially for people in task-oriented jobs.

Next, what resources can you provide in the office that make it easier to get work done? What’s cool? Have you added any support for working families or pets or quiet focus areas? Anticipate objections and clarify the WIIFM (what’s in it for me.)

Finally, even if everyone agrees to come in, no one wants to sit with folks who might be contagious. How can the in-person group work with those who can’t go to the office? How can they include their colleague who moved out of town? What’s the hybrid meeting setup?

3. Provide a clear format for team hybrid working agreements.

Ask every team to complete a hybrid work plan that answers the same questions. At a minimum, this plan should include:

- The days and times that everyone plans to come in

- The key activities they’ll conduct on those days

- The resources they’ll need

For example, let’s say the engineering team decides to come in on Tuesdays from 10 am to 3 pm. They need a big co-working space with whiteboards and display screens, which they use to review the past week’s work and coordinate the next week. They also enjoy lunch together.

A few of the engineers want to come in every day. They need a dedicated workspace nearby so they don’t have to schlep their gear around.

For inspiration, check out these working team agreement templates:

- Gustavo Razetti’s Hybrid Team Canvas

- Atlassian’s guide to creating a Team Working Agreement

- Lucid’s meeting template How to Create a Working Team Agreement

At the end of the next experiment phase, you’ll collect all the team plans and use those to make decisions about the office.

4. Ask each team to run a one-week experiment.

Up to this point, you’ve told teams why you think they should come in and what they can do there, but their deeper objections aren’t entirely logical.

People are resisting coming into the office because it’s easier not to, and they don’t really have to. They’re in the habit of spending the day barefoot.

They need a chance to experience what work could be like if they returned.

This experience has to extend over several days because that first day will be full of “I forgot how much I hate parking here” and “Wow, you’re shorter than I remember” and “What happened to the coffee shop?” and “OMG it’s so good to really SEE you!!!!”

The goal of the experiment phase is for teams to experience what’s easier and harder about working in the office. Here’s a rough schedule:

- Monday: team members reconnect and review the hybrid agreement format. They discuss what they think their agreement should be, and commit to finalizing it at the end of the week.

- Tuesday through Thursday: teams do the work.

At the end of each day, they run a short review where everyone discusses:- What happened today?

- What was easier/better because we are together?

- What surprised us?

- What was harder?

- What might this mean for our work agreement?

- Friday: the team shares a meal and finalizes their plan.

Teams should strive for consensus, where everyone is 80% in agreement with the plan and 100% ready to stick with it. To make this easier, consider adding an expiration date when everyone can revisit this decision.

As the experiment progresses, provide a way for all teams to share what they’re learning and how they’re making decisions. That way, they can help each other solve tricky questions and borrow ideas to improve their own plans.

Hot Tip: Look for the tipping points.

Have you ever visited a new town and gone looking for a place to eat?

Maybe you check some reviews, then head towards a place that sounds promising, only to see that there’s just one person in the restaurant when you arrive. This makes you think “Wow, it can’t be that great after all.”

The next thing you know, you’re heading to a place that maybe didn’t have such great reviews, but seems busy and therefore must be pretty good, right?

The office is just like that restaurant. It becomes the place to be when it’s the place where people are.

While it’s not necessary for every team to run their experiment in the same week, the leadership group should plan to be in the office the whole time so that people can experience the benefits of serendipitously bumping into them. Teams with overlapping work should schedule their experiments for the same time too.

5. Collect the plans and announce the results.

After the teams complete their experiment, you’ll have tons of information about what they feel will help them do their best work.

What a wealth of first-rate intelligence! How amazing is that?

Of course, you may not be able to support every team’s dream plan, but you can get a lot closer now that you know what it is.

This approach also means you can avoid issuing disastrous, out-of-touch mandates. Instead, if you do need to make workplace policy decisions that some people don’t like, you’re doing it based on the evidence provided by the teams themselves.

Research on procedural justice shows that when people can see that a process is fair and that their perspectives were considered, they are more likely to accept the legitimacy of a decision – even when it goes against their preferences. This holds true for workplace policy too.

We get to design a better way of working.

There’s a bright side to today’s broken work. We now know a lot more about how to get work done under rapidly changing and less-than-ideal circumstances.

Now, we get to build brand new working agreements that incorporate the best of what we learned during the lockdowns with the best experiences we can provide when we’re together.

We need to start not with mandates, but by reminding ourselves what that experience feels like.

In summary, if you want people to return to the office, try this:

- Establish a fair process for making these decisions.

- Explain why you believe it matters.

- Gather evidence and build an informed plan.

- Announce the plan.

Does this seem like too much work?

Not when you consider the potential costs associated with:

- Flip-flopping on your policies and losing the respect and trust of your knowledge workers

- Dealing with mass attrition

- Paying for office space that your teams neither want nor need

This is one approach.

Have you found another way to establish a hybrid work policy that people seem to like? How is your company rebuilding that sense of WE? What are you learning during this time of transition?

Please share in the comments so we can all benefit by learning from each other!