Time Management is a Perversion

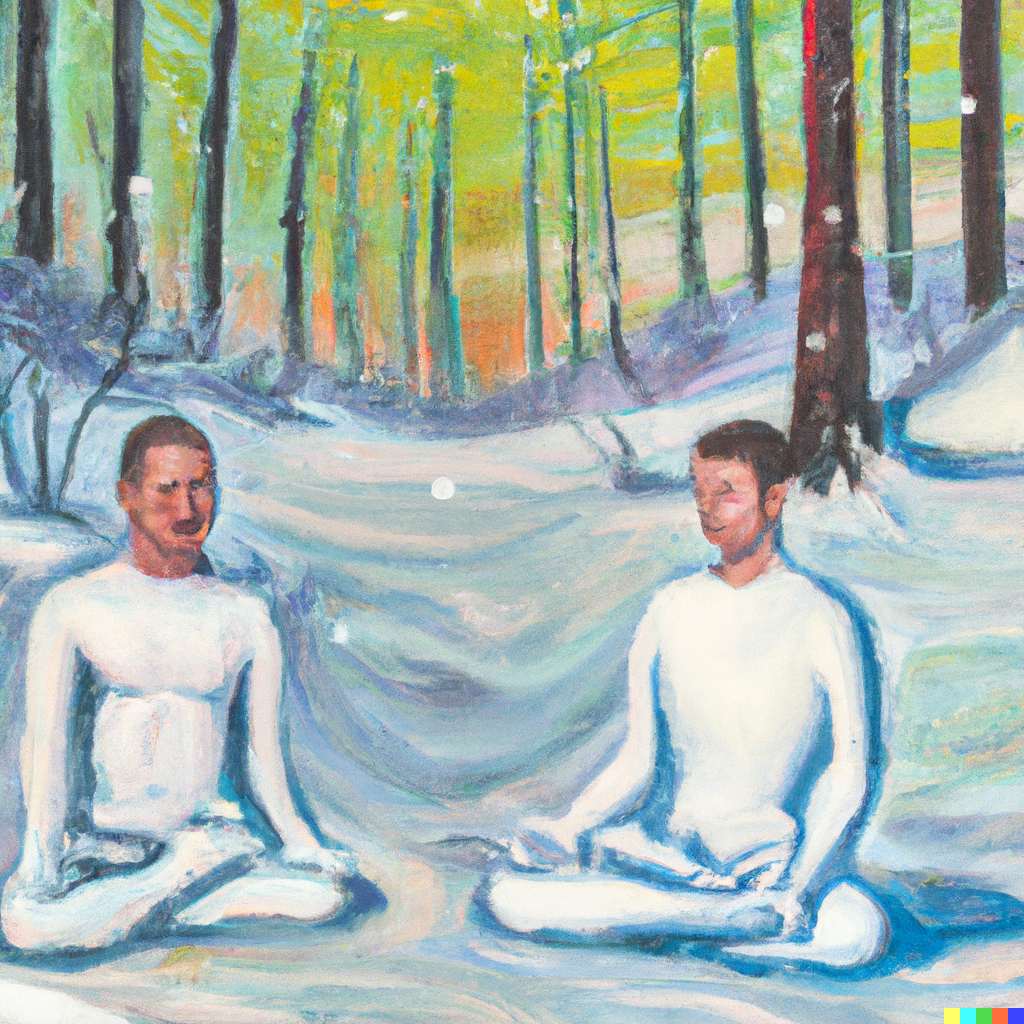

Two people sit mostly naked in the snow, breathing deeply. They remain quiet and still for a long time.

At least it feels like a long time to one of them. The other –

a more advanced student – rests in comfortable contemplation, focusing deeply on sending healing energy throughout his body.

The first one wants to send healing to his body, too. If only it wasn’t so damn cold! As the minutes pass, he begins to fear that bits of him must surely be freezing off. His anxiety escalates until he feels compelled to flee for the warm cabin.

An outside observer would say that these two men shared the same experience. But really, their individual feelings about the time they spent couldn’t be more different.

One experienced a tortuous ordeal.

The other experienced a nourishing moment of calm.

This anecdote, relayed in the book What Doesn’t Kill Us by Scott Carney, holds two lessons for the meeting designer.

Lesson 1:

We cannot control how people experience their time.

The same time is not the same for everyone.

This poses both an opportunity and a challenge.

When we plan our schedules, we pretend that time is linear. We pretend that our activities will fit into these tidy little boxes.

It’s important to recognize the novelty of this idea. Our standards for tracking time (the clock, the calendar, and the notion of shared time zones) are shockingly modern. The 24 time zones we take for granted were first adopted in 1884; it took nearly 70 years for some parts of the world to accept them.

Our experience of time is more ancient and more fluid than our calendars suggest. People have a sixth sense for time.

- Sometimes we feel time as squeezed. Rushing. Frantic.

- Sometimes we feel time as agonizingly dribbling slow.

- Sometimes we don’t notice the time pooled, flowing quietly about us, until we surface with surprise hours later than we imagined it to be.

This fluidity creates an opportunity.

For teams rushing frantically through a hectic day, a few minutes spent silently breathing together can restore calm to anxious minds, and feel wonderfully expansive. You experience more well-being in fewer moments.

When caught doing something we don’t want to do, on the other hand, like sitting too long in an irrelevant meeting, we experience loss. We regret the waste of time and opportunity that we can never get back.

“I need to respect my time,” we say. “I should be charging more for this!” When our perception of who we are meant to be diverges too far from what we are currently doing, we feel we are owed compensation.

In studies of meeting lateness, punctual people were asked how they felt about their tardy colleagues. For some who felt their time was regularly squandered, frustration mutated into rage. As they waited long minutes for others to arrive, they fantasized about their brutal dismemberment.

For good or ill, we experience time as what it is: our most precious non-renewable resource. As meeting designers, our opportunity is to treat time as such.

And that’s our challenge.

Because it’s so very precious, we strive to protect our time. We carefully parcel it out, dividing time into portions that we can place into tidy, color-coded boxes to be neatly shelved on our calendar.

We look at our calendars and believe we’re facing a bin-packing problem. Somehow, if we’re just clever enough, we can fit more productivity into smaller and smaller containers. Then we suffer under the unwieldiness of our clown-car calendars.

Time management, we call it.

The word “manage” means to “control the use of” and “administer, or regulate”. Time management is defined as “the ability to use one’s time effectively or productively, especially at work.”

So here we have the gloriously subjective fluidity of time, and at work, we’re supposed to manage it.

We attempt to manage the floods and trickles and bogs of time by pretending it can be bound by a grid. As if the cage bars of our planning systems are adequate to contain it.

Time cannot be constrained in this way. We cannot control what time will bring us, or how we will experience each time we encounter in our day’s progress.

In fact, the shorthand way to talk about our experience of time is to simply describe our experience. What happened? What did we notice and how did we feel in each moment? That’s the story we tell when asked “How was your time there?”

Experience defies management. We know this.

When someone declares that they’re going to “manage the experience” for a group, it whiffs uncomfortably of desperation; of a need to dictate that which cannot be controlled. We cannot take charge of how another person experiences a moment. We can barely keep hold of our own experience, let alone someone else’s.

Attempting to manage other people’s time is perverse.

This is never more evident than when reviewing meeting feedback. In every workshop with more than twenty people, there will be three who rave about the wonderful experience, four who think it was pretty good, two that hate it so much that they wish ill on the facilitator (and their family and town and …argh, burn it all!), and a majority who decline to comment.

I can’t control how someone else experiences a meeting. Neither can you. That’s ok.

In the self-help literature, we learn that if we want to experience a better life, we should balance intentions with acceptance. Decide who you are when you are your best, then become present to the experience you’re having. Accept now for what it is, bring your best available self to this moment, and find peace as you dance with it.

We seek to craft our perception, clarify our intention, and adapt gracefully to each experience in a way that stays true to our deeper purpose. This is the work of the parent kneeling to share delight in a bug with a baby, and of a deep breath taken to block harmful words safely behind the fortress of a closed mouth. This is what we do when we make simplifying rules, like no alcohol on weeknights or meetings on Fridays. The more we clarify our intentions and tune into the current moment, the more adept we become at preventing harm and relishing delight.

This is the work of the half-naked man meditating in the snow. The work is not about control, but about intention, acceptance, and adaptation.

That brings us to lesson 2.

Lesson 2: What we repeat determines our experience.

The mere repetition of a behavior causes our nervous system to believe that the specific actions involved and the context in which they are embedded are important, for better or worse. Choose what you repeat wisely.

Andrew Huberman, neuroscientist and Stanford professor of Neurobiology

Experiences cannot be controlled, but they can be designed. Both from the individual and the group perspective, experience design is a way of intentionally crafting a person’s future experiences.

Wim Hoff, who challenges students to meditate in the cold, aims to shape their nervous systems to adapt and thrive in extreme conditions. He can’t control who shows up or who will stay through his whole program, but he can design the experience to increase the odds of success.

User Experience Designers craft the layout and flow of products, anticipating user needs and actions, then building products that attempt to increase the likelihood that users will enjoy the desired experience.

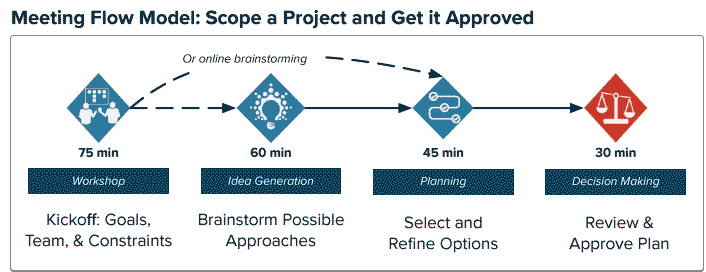

Meeting experience designers craft the setting and sequence of events for group gatherings, increasing the likelihood that the meeting will yield the desired results.

Attempting to manage experience is pitiable; crafting experiences is aspirational. The first is a sad control freak, the latter an artist, expert, designer, guru, and professional.

Crafted experiences + repetitions = transformation.

As Dr. Huberman noted, for better or worse.

And yet, when most leaders look at their team’s calendar, they think in terms of time management. How can the group achieve more in less time? How can we manage the time so we’re focused on productive work?

If time is our way of describing and measuring a collection of experiences – all those repetitions – why do we think it can be “managed”? Why do we talk about time management as if that’s a moral high ground rather than an anxiously inadequate perversity?

Time, like experience, defies management. To pretend otherwise breeds false expectations that can only be disappointed.

I believe we need to let the idea of time management go.

Our calendar-cages serve an important coordinating function, but that’s the limit of their power. For our time to bubble with the experiences we seek, I suggest we focus instead on time crafting.

Time crafters root in purpose, not fear of loss. They focus on sowing radically redundant opportunities to become better, rather than on ways to squeeze productivity out of each twist of the clock.

Time crafters walk their paths hand-in-hand with both serendipity and responsibility, leaving control behind. Time crafters invite, guard, inspire, and support. They don’t manage.

Time crafting is about looking at the future as an opportunity to design experiences worthy of our most precious non-renewable resource.

Meeting System Designers are Time Crafters.

Meetings provide the first, the most frequently repeated, and the most pervasive opportunity we have to shape our team’s beliefs regarding which specific actions and contexts matter. If we don’t talk together first and foremost about the work laid out in our mission and vision, those things don’t happen. By contrast, teams that take time in each meeting to update a big chart tracking their progress toward a big goal are more likely to achieve that goal.

The way we meet determines our experience of our time together.

As we meet, day after day and week after week, those repetitions will change what feels comfortable and what we are capable of doing together. If how we speak to our coworkers and our customers during meetings doesn’t match up with the values poster up on the wall, it becomes uncomfortable to live those values. If, on the other hand, we practice sharing appreciation, or direct feedback, or learning in each meeting, that becomes an increasingly comfortable thing for teams to do.

When we intentionally design our meetings to repeat in ways that enhance our culture and propel our work, we feel the time spent in them as rewarding. We may feel accomplished, valued, smart, and like we belong. We may find ourselves smack dab in that wonderful intersection of playfulness, connection, and flow that Catherine Price found to be the most accurate definition of fun.

Don’t believe it’s possible?

If so, you’ve been in the wrong repetitions. A team that’s wrapped in a blanket of banality and PowerPoint can’t imagine meetings that challenge or push or delight them. Their nervous system has adapted to meetings that they do not enjoy, and now they’ve come to believe that the specific actions involved and the context in which they are embedded are important.

This team needs new experiences. It is possible. Many groups have designed a system that makes their meeting experience better. They repeat practices that help them become the teams they aspire to be.

I invite you to ponder this perspective shift. Shake off any old beliefs that somehow, if you just adopt the right productivity system, you can manage your way to a better life. Stop trying to manage your team’s time, too.

Instead, become a time crafter. Think of how you might design your time to bring you excellent experiences. Prioritize activities that more people are more likely to experience as meaningful, connected, and fun. Consider the skills and language your teams would repeat if you were living up to your intentions, then craft a system that builds those repetitions into your meetings.

And good news! Once you have an idea of how that might work, implementing a meeting system doesn’t have to be difficult.

After all, it’s not like anyone’s asking you to meditate half-naked in the snow.

Techniques for Time Crafting in Meetings

What feels short and what feels long?

Which tools and techniques can we use to adjust timefeel?

Beyond the adaptation that comes with repetition and fluency, what other factors influence our unique experiences of time?

We’re exploring these questions in the Meeting Innovation Community, and invite you to join the conversation.