Getting Work Done in Meetings: Structures for Success

Leaders get work done through the conversations they hold. Often those conversations are in meetings—particularly when multiple people need to be in the discussion. In spite of all the criticism of time-wasted in meetings, leaders need meetings to create new insights, build understanding, and make decisions with their teams.

As a leader, you can choose to make your meetings more effective by understanding how to structure them and when to hold them to accomplish real work together. Effective meeting structure is the key.

Structure?

Most prescriptions for better meetings focus on changing behavior. But most leaders (and their teams) find it hard to adopt and maintain different behaviors under the pressure of important discussions (and few have a facilitator to help them “talk nice.”) Instead, leaders can change the way their meetings are structured to make them naturally more effective. “Structure” refers to various physical, temporal and procedural variables that influence how people talk together. The right structure naturally supports more effective behaviors and leads to productive use of participant time and expertise. Here are three structural changes you can make to your meetings to improve the quality, efficiency and outcomes of the work you need to do in your meetings.

Three Structural Changes

There are a number of choices you can make to create an effective structure for your meeting. Here are three of the most fundamental.

1) Deciding whether to hold a meeting.

Too many meetings are scheduled for a set date and time period with little consideration for what needs to be accomplished with whom and for how long. Should the “weekly” team meeting really be weekly? Or last for an hour?

Before you hold any meeting, ask yourself “Do I expect some tangible result from this meeting?” Unfortunately, many meetings lack a clear definition of the work to be done. For example, consider an item listed on the agenda as “communication planning.” One participant may think it refers to email policy while someone else believes it refers to marketing. They can’t come prepared and may talk at cross-purposes. Consider how much more efficient and effective the discussion could be if the agenda listed the intended task as:

To develop a better means of communicating quarterly results to our staff so everyone can see how this information is relevant to their responsibilities.

A meeting worth holding should have one or more clearly defined tasks to accomplish. Each task should be:

- Focused: This is the work you’ve called this meeting to accomplish. If you have “updates” on the agenda, consider whether these are work you need the group to do together or whether information sharing is better handled by some other means.

- Actionable: The work to be done can be acted on by those present (not referred to someone else). This should not be a theoretical discussion, but something that participants have direct personal involvement in resolving.

- Timely: This is the appropriate time to address this topic. It is important (and possibly urgent) that it be addressed in this meeting.

- Timed: A realistic amount of time is assigned to complete this task given the size of the group and how you plan to involve them in any decisions.

I’ve had some people ask if I assume meetings are just for decisions. My general answer is “yes” in that meetings are most suited to making decisions or reviewing the progress/outcomes of past decisions. Rarely should meetings devote much time to general “updates.” Updates can be handled through written memos or reports and shared in advance with meeting time reserved only for questions.

2) Choosing who should be present.

Many meetings are held with “the usual suspects,” but do these people have all the necessary information and insights? And are they the ones who will implement any action plans that arise from the meeting? I learned a great way to remind myself of who needs to be present from authors/consultants Marvin Weisbord and Sandra Janoff (2007). They suggest identifying participants as those who ARE IN as they have:

- Authority to act,

- Resources relevant to the task,

- Expertise,

- Information, and a

- Need as they will be impacted by the decision.

Sometimes a larger meeting is the best choice to ensure good implementation and follow-up— as long as it is structured so all can participate.

3) Choosing how you will build decisions.

Effective discussions should build alignment if not full commitment to decisions, but often this is not the case. One reason for this can be differing participant assumptions about how any decision is to be made. For example, participants may assume they are providing input to the leader’s decision, while the leader assumes he/she is gaining their commitment to any decision. Such conflicting assumptions affect participation and lead to poor implementation (as Steven Rattner documented about GM’s meetings in his 2010 book, Overhaul).

You can avoid this problem by being clear about how you want to make a decision with your group and conducting the meeting to reflect that approach. Different agenda items may need different approaches. There are five basic ways to involve a group in making a decision. Each can be best in certain situations and some are more appropriate in certain organizational cultures.

- Consensus: Everyone fully supports the decision.

- Consent: Everyone supports the decision as “good enough.”

- Compromise: Each person gives up something to reach a decision.

- Counting (votes): The “side” with the most votes wins the decision.

- Consult: The leader wants the group’s input, but makes the final decision.

Beginning to Change Your Meetings

I suggest you begin by reviewing a recent meeting.

- Did the agenda clearly specify the work to be done?

- Was the timing adequate for the type of discussion you had?

- How many people were there?

- Did you have all the necessary people present for implementing key decisions?

- Did everyone have a chance to share his/her thoughts on key points?

- And most importantly, did the meeting produce desired results?

These questions will help you see what worked and what you can try to change for better results. Then choose the easiest structural change for you to implement and try it out next time.

Resources

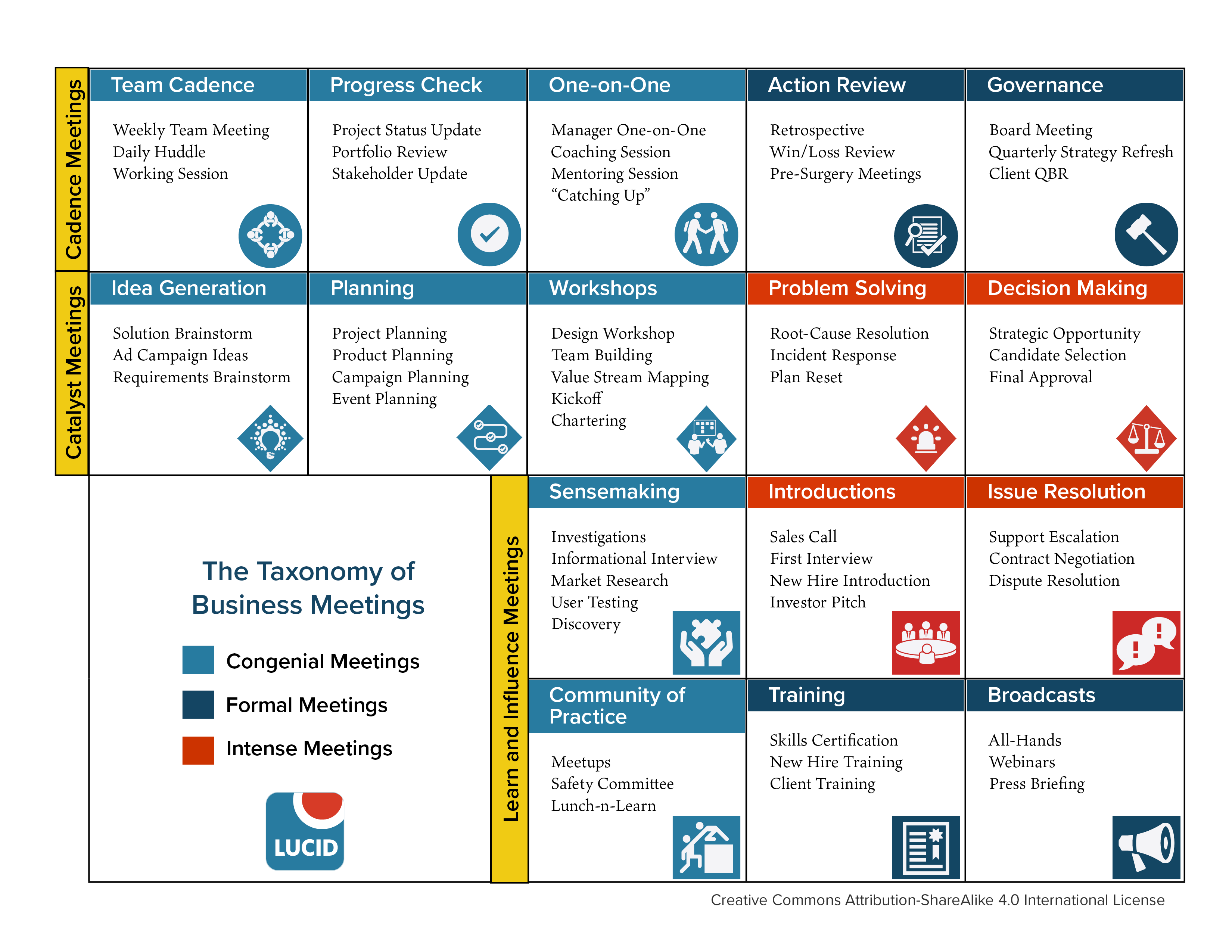

For more information on a structural approach to better meetings, see my new book, Leading Great Meetings: How to Structure Yours for Success. This book is designed to help leaders everywhere conduct a wide range of meetings from team meeting to board room. It provides 12 choices and 32 tools along with stories and examples to help you recognize and change meeting structure.

Structures for Making Decisions With a Group

Gathering Productive Feedback

You can also try an example of a ready-built meeting by using my new template for Gathering Productive Feedback, developed to work either in Lucid Meetings or to download for use anywhere. Like all templates in the Lucid Template Gallery, this template provides an initial framework for an effective meeting that you can build on.

References

- Rattner, Steven, Overhaul: An Insider’s Account of the Obama Administration’s Emergency Rescue of the Auto Industry. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010.

- Weisbord, Marvin and Sandra Janoff, Don’t Just Do Something, Stand There!: Ten Principles for Leading Meetings That Matter. San Franciso: Berrett-Koehler, 2007