Make Better Decisions Faster by Standardizing Your Decision-Making Criteria

Note: These criteria were originally shared as part of our guide to establishing an effective decision-making process.

Have you ever responded to a Request For Proposal (RFP), with its pages and pages of Musts, Shoulds, and Nice to Have selection criteria?

Or, let’s keep it simple. Have you ever worked with your team to decide where you should go for lunch?

If you’ve ever chosen between multiple viable options, you’ve used decision-making criteria to make that choice.

Or maybe not? Maybe you and your team acted out this scene?

With many decisions, the criteria feel obvious and/or automatic.

When deciding where to go for a quick lunch with your team, you’re picking somewhere nearby, somewhere not too expensive, somewhere fast, and a place serving food everyone in your group will eat. At my office, that narrows it down to about 20 places (hurrah, Portland!).

Once we’re narrowed down to 20 or so dining options, we get into secondary criteria. Do we know the owners? Have we eaten there too often? How’s the ambiance, and the service? Finally, (or first) what sounds good right now?

We know how to establish and evaluate criteria for decisions like this. We’re not always very good at it, but that’s human bias and emotion for you. Can’t trust it to make optimal decisions, and you can’t make any decisions without it. (For more on this, read The Leader’s Guide for Making Decisions in Meetings – Part 1: The Science of How We Make Decisions)

But how do you determine criteria for your organization’s big decisions? Our little lunch example already includes eight criteria, and it’s not a big decision! When you think of all the possible criteria you could analyze for those big ones, it quickly gets out of control.

Let’s consider for a moment the RFP example – a process that seems like a good way for organizations to be responsible with their money. In reality, the RFP process often costs WAY more time, effort, agony, money, goodwill, and delay than it ever saves. So, to move things along, everyone involved learns how to “work the system” – thereby defeating the purpose of the system in the first place.

There are three ways you can avoid this analysis paralysis.

1. Define minimal criteria for each big decision.

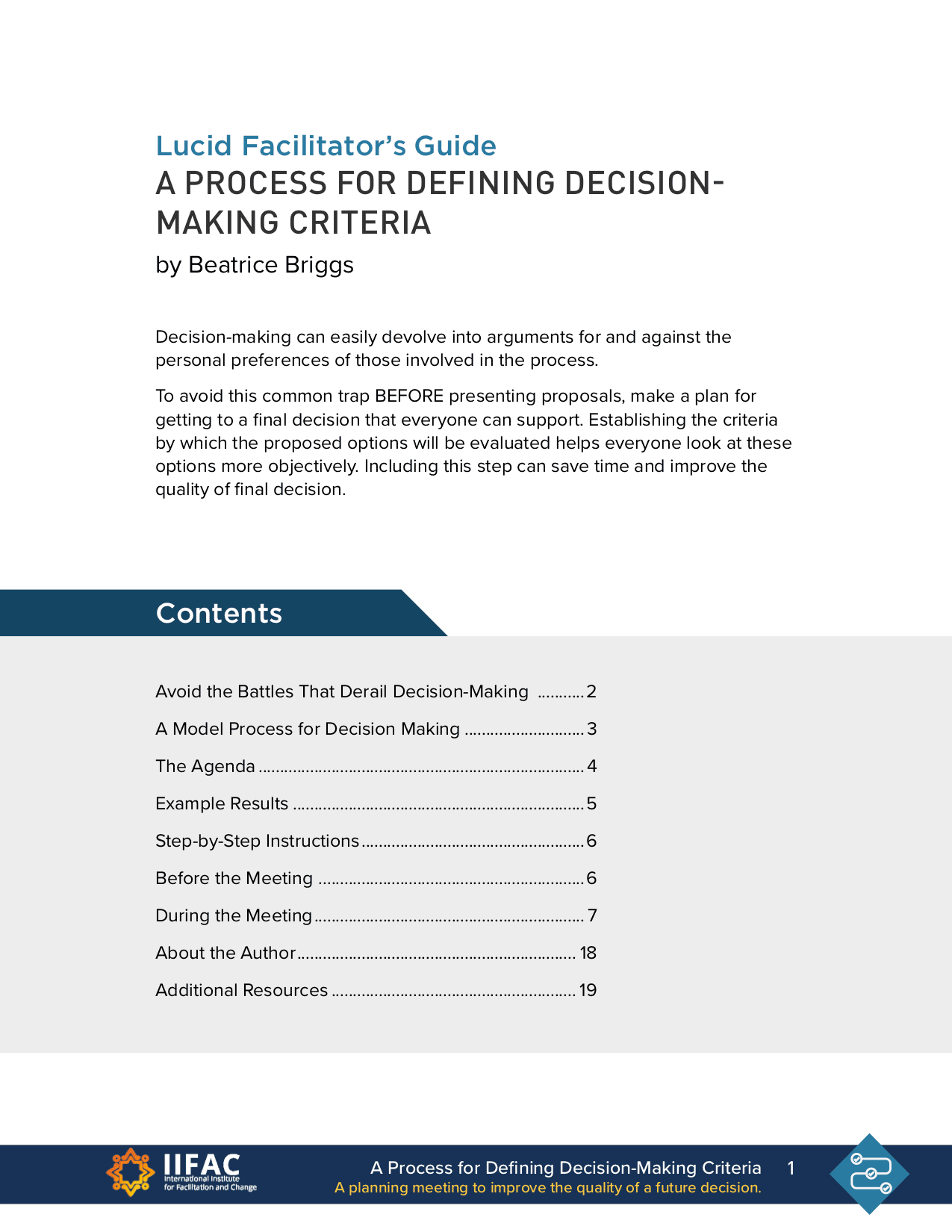

This template by Beatrice Briggs walks you through how to do that with your group.

2. Use a predefined decision-making framework.

Most frameworks include some predefined criteria and some process steps that help a group work through those.

Need examples? You can browse several frameworks in these articles. But be forewarned; there is a mega-internet-level rabbit hole lurking behind each one, so block out some time and get ready to explore the wonderland.

- The 6 Decision-Making Frameworks That Help Startup Leaders Tackle Tough Calls on First Round Review

- Deciding How to Decide by Hugh Courtney, Dan Lovallo, and Carmina Clarke for Harvard Business Review

- Peruse MindTools section on Decision Making

- Grab a carrot and run a search on “Decision making in your sector.”

e.g., “Decision making in hospitals”, or “Decision making in intentional communities”, or “Decision making in sales teams.”

3. Keep it easy and use our all-purpose decision-making criteria!

I’ve been down the rabbit hole, and I can tell you that it’s full of cake and potions that never get it quite exactly right. Every framework works way better than winging it, but they also struggle to find the right balance between irresponsible brevity (too short!) and analysis paralysis (too big!).

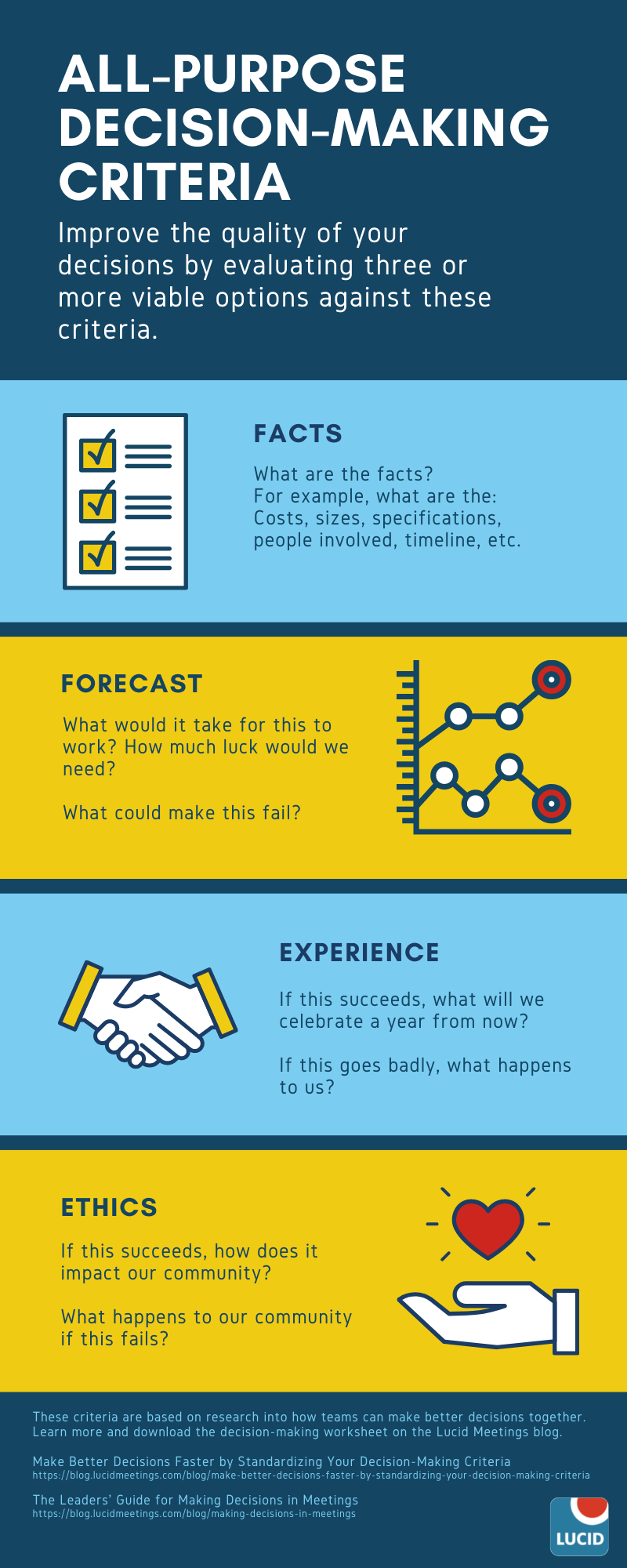

After reviewing these frameworks and the techniques researchers found most likely to improve decision-making quality, we decided to standardize on a set of all-purpose criteria that we can use to make 90% of our big decisions with confidence.

We settled on this specific set of criteria because they’re flexible, giving you room to scale up or down the amount of detail you bring into the decision-making process, and they work well when evaluating the options for all kinds of very different decisions.

Here’s how it works.

Once you’ve identified at least three viable options, answer these questions for each option.

Why these Criteria Work

Facts

- What are the facts?

You’re looking for objective logic-feeders like costs, size, who’s involved, timeline, etc. We leave this section intentionally generic so that the people making the decision can choose the facts that best support the decision at hand. You’ll see how this plays out further on.

Writing down and reviewing facts ensures everyone involved in the decision understands the options in the same way. It’s shocking how often people don’t realize they’re talking about completely different things or looking at entirely different facts, and this helps avoid those kinds of misunderstandings.

This activity also highlights individual biases, as the facts each person chooses to include reveals the way they perceive that option and the decision.

By the way, these individual differences are a very good thing!

There are always more facts than any one of us can care about, so getting everyone’s version of the “facts” on the table means you get to benefit by learning from all those unique perspectives.

Forecasting

There are two questions here:

- What would it take for this option to work out? How much luck would we need?

- How might this totally fail? What could happen that would make this turn out badly?

We have a natural tendency to be optimistic about things we want and to rationalize (i.e., make something up) that justifies why we should get it.

Forecasting the literal steps it would take to make something work helps bring in some realism. Do you have the time and resources to pull this off? If the option you’re considering relies on one of those “a miracle occurs here” steps, that’s good to know in advance.

Forecasting how a plan could fail helps point out obvious risks. It also creates the foundations for better planning, because you can plan to avoid those failures upfront. This technique — deliberately exploring the possibility of failure — is known as a “premortem” and research has proven it to be one of the most effective techniques for improving decision quality.

Experience

We hope to evaluate options using logic, but we ultimately make decisions using emotion. Picking 3 options, then outlining facts and forecasting helps bring some logic to the decision.

The experience questions now deliberately tap into the intuitive wisdom locked in our emotional centers by helping us get clearer about our vision.

- If this succeeds, what will we celebrate a year from now (or whatever the timeline should be)?

- If this goes badly, what happens to us?

Vision (literally the seeing-things kind) is the strongest sense in the brain, and when you envision celebrating, you can often “see” details of the plan in your mind that make it clearer what steps you’d need to take to get there and whether that party is really worth the effort.

We also practice envisioning success because it can clarify the underlying reasons why we might be drawn to one option over another. It helps us find the deeper “Why?” behind our wants.

For example, let’s say you’re thinking about buying a bigger car. If you envision that success means you’ll take more comfortable trips, you might realize that going on trips is what you really want; not the car. When you get clearer on the underlying values and needs driving this decision, you can consider other ways you might go on trips (which is what you really want to celebrate), opening up options that may cost less and save you space in the driveway.

Then, dig into what it would be like to experience failure. This helps make the consequences of a bad decision personal; if this goes bad, what happens to me? We don’t like to think that our plans could end catastrophically, and this question forces us to acknowledge that possibility.

Most people are naturally risk-averse, so you don’t need to spend too much time here. Just make sure you’re balancing your enthusiastic vision of success with an awareness that success is not guaranteed.

Ethics

The questions about ethics root your decisions in your values.

- If this succeeds, how does it impact our community?

- What happens to our community if this fails?

The facts, forecast, and experience questions all make the impact of the decision clearer to the people making the decision, but they don’t take into account how that decision might impact anyone else.

For some groups, these questions never come up. For others, they talk about community impact all the time and don’t talk enough about the facts or how they’d be impacted personally.

Dealing with the ethics question separately makes sure it gets addressed and helps put it in balance with the other decision-making criteria.

Want to learn more ways to discuss ethics at work? Check out HBR’s article on Building an Ethical Company

How to Use These Criteria

Here’s what we recommend.

- Answer the questions individually for each option.

Each person involved in the decision-making process answers the questions individually before the meeting. Try to keep the answers short. Use bulleted lists or simple phrases; just enough to capture your ideas. When you’ve finished looking at all three options, review your answers and refine them.Here’s a simple decision-making worksheet each person can use to capture their answers to these criteria.

- Share your answers. Read everyone’s answers before the meeting.

- Discuss your answers during the meeting. Then, make the decision!

Share and compare everyone’s answers. Make it easy by giving everyone 5 silent minutes to revisit the answers again and jot down anything that strikes them. Then, start talking about what you see. The decision is made after discussing what you all discovered through this comparison.

Now: Let’s help each other make better decisions

We all know that taking the time to think through our options and discuss them as a team can lead to better decisions. The quality of the decisions we make determines much of our later success. Hire the wrong contractor? Your project fails. Expensive student loans, low-salary career? That’s a decision that will haunt you for a while.

But in reality, we rarely take the time to complete even the most basic analysis.

We’ve shared these decision-making criteria in a hope that you’ll be inspired to try them out. Maybe download the spreadsheet and fill it in for a decision you’re facing in your personal life. If you do, we’d love to hear:

- What did you learn in the process?

- What improvements would you recommend?

Our goal is to make it as easy as possible for teams to run successful, high-quality decision-making meetings every day. We’d love your ideas about how we can all better achieve that goal.