The Story Behind Our Meeting Flow Model for Pilot Programs

It doesn’t matter what kind of team you work on or what you’re trying to do – if you can’t get that team to all agree and do their part, you fail.

Teamwork is the practice of agreeing on a shared goal and then dividing the work required to achieve that goal amongst the team members. To get that agreement and coordinate all that doing, you’ve got to communicate.

We’re coming up on our 10th anniversary here at Lucid, and over all those years, we’ve done our fair share of failing. One of our more painful failures came about through a failure to effectively communicate.

We ran an enterprise software pilot program with an organization that didn’t have a clear understanding of which problems we could help them solve and which we couldn’t. (Not sure what a pilot is? I’ll explain it below.)

That pilot failed.

Afterwards, the organization leaders told us “You know, if we had started out with the right expectations, we know this would have been a slam dunk.” Ouch.

I know failing is something we’re supposed to be proud of these days.

I know we’re all meant to be failing fast and failing forward, gathering hard-but-necessary learning along the way. Sometimes, though, you fail because you didn’t have what it takes to succeed and there is no second shot. Failure can be educational, for sure, but it can also be just one more nail in the coffin. I’d much rather design for success.

We’ve had plenty of successes here too, of course – I wouldn’t be here to share this story if we always failed. We’re currently running enterprise software pilot programs that are moving along nicely, in a large part because of the work we did to think through the communication requirements for these programs and design a Meeting Flow Model to support them.

In this article, I’m going to share that MFM and some of what we went through in designing it. Look at this as an example of how you might go about creating MFMs in your business. This is the third article in this series. The first two articles provided an introduction to Meeting Flow Models (MFMs), so if you haven’t seen those yet, go ahead and skim them now.

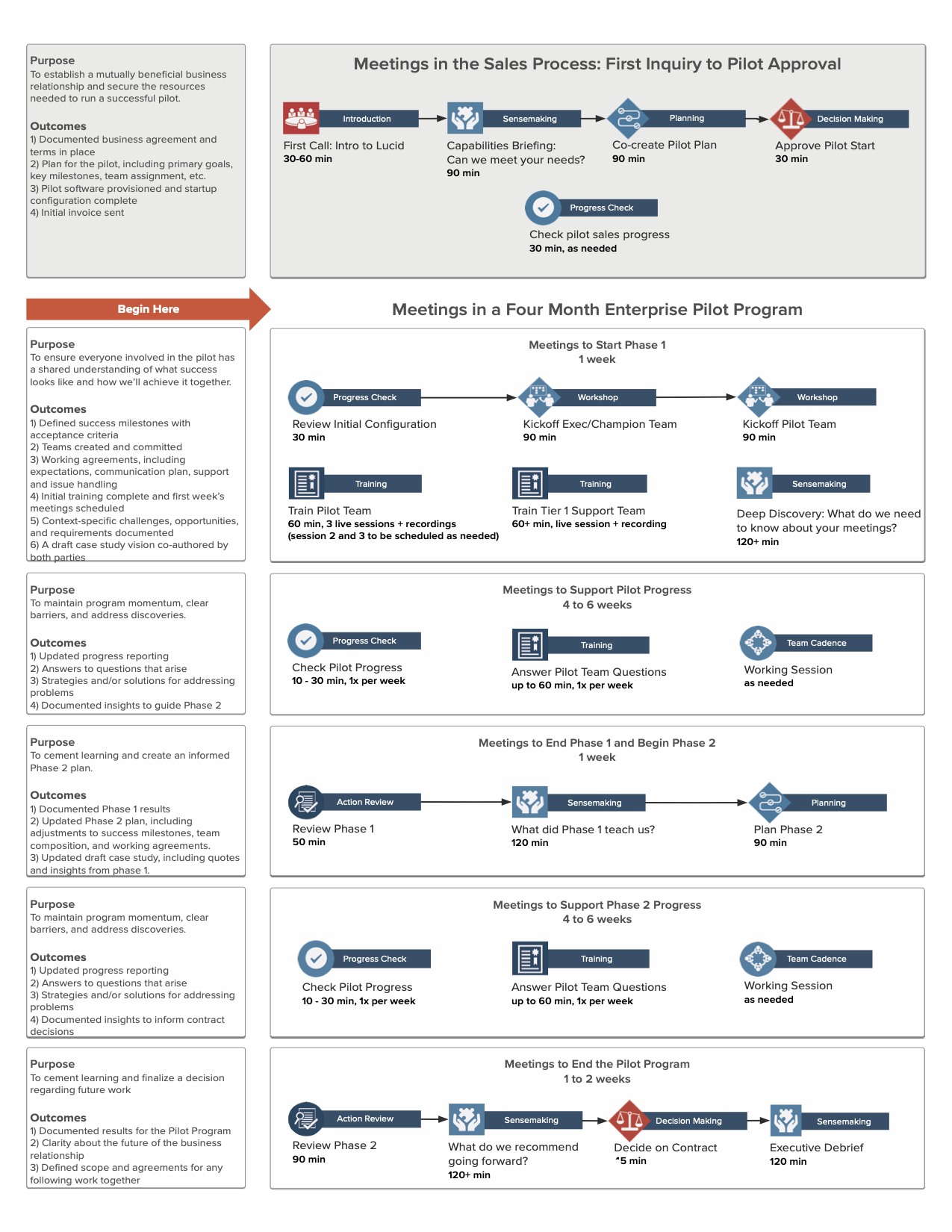

The PDF below is our MFM’s guidebook. We also developed meeting templates, worksheets, tracking systems, draft presentations, and other collateral to support these programs which I’m not sharing here.

Check Out our Pilot MFM Guide (PDF)

Important Note:

This model is used to support our teams as they work; it is not meant to force anyone into a following a rigid process. While some simple business processes can and should use prescriptive MFMs, complex multi-stakeholder learning projects like this one should be guided rather than constrained.

Um, what’s an enterprise software pilot program?

For those of you who don’t work in the technology world, software companies run pilot programs to help a new customer start using a complex software product. These programs typically involve lots of configuration, training, development and/or design work, communication planning, and business process change.

In our case, because our software impacts the way teams run meetings, the software has a significant impact on how those teams do their everyday work. While there’s absolutely a lot of technical work involved in a program like this, success hinges more on the customer team’s ability to change their meeting behaviors. That behavior change needs to be guided with lots of training, coaching, and support.

Pilots are not free trials. Customers pay to run a pilot. In some cases, the pilot period is just the first several months in an annual contract. In our case, we wait to sign a contract until near the end of the pilot program so both we and the customer can be confident that the relationship will be a good one.

Because we have large dollar contracts depending on the success of these pilots, and because each of these pilots requires an investment of expensive resources on our side to run, the meetings we hold with our customers during the pilot really do make or break our organization.

How We Built This MFM

We built this model from scratch. As I mentioned in the previous article, you can also find pre-designed MFMs to bring into your business, which is much easier.

To create a brand new MFM, it’s helpful to know these things:

- Why teams meet

- How often you might need to meet

- The other communication mechanisms available to you and when to use them (email, reports, chat, etc.)

- How to run and design an effective meeting

- The different types of meetings you might need

Triple bonus if you also know a handful of fun, productive meeting techniques.

Creating Version 1 of our MFM

We’re all over this stuff and we’re also keenly aware of what an amazing advantage a good MFM can be, so you’d think creating this model would have been one of the first things we tackled. We’re Lucid Meetings, after all!

You’d think – and you’d be wrong. Just like it is with all those gorgeous people partying on Instagram; the reality behind the public face is always messier than we’d like.

In reality, we started work on this MFM after our painful pilot failure. The first version was a bulleted list that looked basically like this.

- Kickoff with Champion

- Kickoff with Pilot Team

- Training

- Progress check meetings

- Customer interviews

- Decide on Contract

Our key learning was that without a good kickoff, the pilot was at risk. We knew that if the customer’s pilot team wasn’t super clear on the problem we were trying to solve and what success looks like, we’re in trouble.

This list was definitely better than nothing, but far short of complete.

Version 1 in Action

When our next pilot came along, we talked repeatedly with the customer team about the importance of scheduling a kickoff. They nodded along for awhile, but as we got closer to the projected start date, they pushed back. They just couldn’t imagine getting all their people together in a room for two-full hours just to talk about a software project.

Insisting that this was our process— even reworking the bulleted list into a pretty flowchart— proved unpersuasive. Instead of the facilitated kickoffs we’d asked for, we ended up running a series of disjoint virtual meetings with a rotating cast of pilot team members.

This pilot didn’t fail to reach a contract, but it did take nearly double the time to complete, making it wildly unprofitable.

So finally, with one failed pilot and one that was costing us too much, we made ourselves step back and put in the time it takes to do the job right.

Questions We Faced When Making Version 2

To be fair to our younger selves, we didn’t fully recognize what a solid MFM could and should include before. It was only by trying to document the meeting practices of elite teams that we began to fully realize how all these meetings were related, and how that–when you lay them out into a flow–you can suddenly see the patterns that lead to success.

Once we knew what a great MFM needed, we could mature our list into something more powerful. For this project, that meant answering a whole lot of questions concerning our vision for these programs and the critical success factors we should build in.

As a small company CEO and the official Meeting Maven, answering these questions was primarily my responsibility. I had to pull out both my business and meeting-designer hats to do the job.

Question 1: When and how should this program begin?

Business Hat

Business Hat

When does a project like this officially start?

What can I count on having done before we begin?

I remember talking with an engineer one day who was getting burned out on a long project. “When will the software be done?” he asked. Fortunately for us all, we’re never really “done” when working on online software. If we do it right, we get lots of customers who want to pay us so we can show up and do it some more for years and years and years.

The same is true of great customer relationships. We have some clients we’ve been working with for nearly twenty years now. To create programs that we can design and run profitably, we need to create key moments in what is otherwise a long, continuously evolving relationship.

For this program, we decided it begins once the software was ready for the pilot team to start using in real meetings. All the meetings where we figure out when this program will start, who will run the tests, and what color to make the buttons are now part of our Pilot sales process.

Meeting Designer Hat

Meeting Designer Hat

What does the science have to say about inspiring new teams and building commitment?

What do we know about meeting patterns in successful projects?

There’s a ton here that’s worthy of a separate article.

Short version:

- Teams working towards a shared vision of success have a better shot of achieving that success. What’s more, they’re more likely to be committed to that vision if they created it themselves. So we need to support that co-creation up front.

- Teams work with better focus and energy when they feel a sense of urgency. The research suggests people don’t feel this urgency until after the midpoint of any project. So, to avoid rushing all the work into the last possible minute, we need to create critical milestones throughout the program.

Question 2: How can we make sure we’re investing time wisely?

Business Hat

It’s crazy hard to get time on everyone’s schedule. How can I make investing this time efficient and compelling?

For this, we run the numbers and then iterate. We have a calculator built into a spreadsheet for these programs that shows the total amount of meeting time we’ll spend together. When planning the program, we can pull up this calculator and adjust the numbers.

For example, we anticipate that pilots will last anywhere from two to four months. The overall duration depends on how many stakeholders need to buy in and how often they’ll be able to run real meetings using the software. It’s in everyone’s interest to make these pilots as short as possible, so tightening this up is part of what we do in the planning process.

Here’s another example. Let’s say that the customer doesn’t want to commit to a weekly progress check meeting. With our calculator in hand, we can talk about alternatives. What if we shared updates by email instead? Or in our project system? How long would that take? Can we really count on it? Alternatively, if everyone commits to updating their information in advance, how short could we make that meeting? Can we get it down to 10 minutes? Often we can.

Secondly, we compare the time spent when we follow the recommendations versus what happens when we don’t.

For example, I mentioned above that one of our recent pilots decided they couldn’t commit to the kickoff meetings and discovery sessions in that first week, and we acquiesced.

Big mistake. Instead of 8 hours spent in meetings over the course of one week, we ended up adding two whole extra months to the program and over 30 hours of EXTRA meetings.

On the bright side, we sure learned a lot! And now we’ve got data to back up why we stick to the plan for future pilots.

Meeting Designer Hat

Which meeting practices can get us the outcomes we need most quickly?

To answer this question, we start by making sure we’re crystal clear on the desired outcomes for each meeting. Then, we can draw on all the meeting techniques we’ve learned over the years to find the ones that get us those outcomes fast.

We then design those ideas into our meeting templates. For these pilot meeting templates, we also include a few alternative techniques for each meeting because we can’t count on the people on the customer’s side having any training or practice in meeting skills.

Meetings are a team sport, and in these meetings, we have to anticipate that many of the players will be super new to the game. That means that the theoretically fastest performance isn’t actually an option. Instead, we need designs that give us the fastest performance available to a beginner team.

Question 3: What kind of relationships do we need to build and how can we do that?

Business Hat

How can we make sure we’re building the business case and success metrics we need to secure a profitable business relationship?

The goal of this program is the creation of a mutually beneficial long-term business relationship. That means both parties will be gathering evidence throughout the program – both hard data and stories – to help us all make a decision about that relationship.

If we do our job well, this decision should be no-brainer obvious for business leaders in both companies because we have great data in front of us. In our meetings, then, we need to make a point of capturing the stories and the data throughout the program so by the end, we’ve got the business case ready because we’ve built it all along the way.

Meeting Designer Hat

How can we ensure the team works well together given the probable differences of knowledge, perspective, need, and lack of established trust?

Relationships and trust take time to build, but teams that share stories about who they are, what they care about, and how they see things build that trust more quickly.

Leadership coaches and facilitators use lots of techniques to help break down silos and repair relationships within companies. We can borrow from these ideas to help form great relationships up front.

Question 4: What kind of resources will we need to pull this off?

Business Hat

What kind of resources will we need to execute on this program?

Do we have enough of the right people with the right skills?

There’s a difference between what it takes to get the most amazing optimal result you could ever imagine, and the result you can get with the resources you have.

While outlining this MFM, we constantly looked to see how we could do more with less. Efficiency increases the ROI for both us and our customer.

That said, we’re more concerned with excellence. Because we aren’t willing to sacrifice quality for efficiency, we also now know our current limits. We can only run so many of these programs at once with our current staff.

To run a whole lot of pilots at once, we’d need more people. Now here’s another benefit of this MFM: it makes it way easier for us to get new people up to speed. The MFM gives newbies a complete playbook for how to succeed with these program meetings.

Meeting Designer Hat

What kind of resources can we prepare in advance to make the meetings feel magically easy?

How much of the preparation and follow-up can we automate?

Whenever possible, we want to make the work about filling in the blanks rather than having to figure out what to do from first principles.

Here’s an example. In the software industry, companies share customer success stories in the form of case studies. There’s a standard format for every case study:

- The customer’s problem

- What they tried before that didn’t work

- How they found the software

- What it was like to start using it

- The results, or how the customer’s life is better now

When we work with our customers in those first kickoff meetings to create a vision of success, we could have an open-ended discussion about that success. We could use success story formats from academia or the design world by writing our own headlines or creating a vivid vision of our dream world. But since these programs are specifically about solving problems using software, we don’t need to invent a format. We can start with the case study standard.

Then, in our kickoff, we don’t have to figure out what questions we’re asking or what format we’ll use to document the answers. We just have to fill in the blanks with the customer’s specific problems, what they tried before, how they found us, what we did together, and what we all believe the results will be.

The Big Question: How can we make this the most valuable and enjoyable experience possible for everyone involved?

This is the question that matters to all the hats and should be the concern of every leader for every MFM.

Work should feel good. We want our teams to love what we all do.

They should feel appreciated for the hard work they put in to helping the pilot teams run successful meetings, and they should feel proud of the meaningful difference they’re making in people’s lives. It’s not always joyful and it’s rarely easy, but we should feel good about what we’re doing in our time together.

We want our customers to be delighted. We want them to develop a perspective and skills that will make their meetings better not just for today, but for the rest of their careers. We want to help them develop pride in their meetings, too.

We all want to have fun. When we design the meetings we’ll spend so much of our lives attending with this in mind, work becomes more enjoyable for us all.

Wow, ok. Oversharing there a bit, aren’t we?

I haven’t written about Meeting Flow Models in this level of detail before. I’m sure in the future, we’ll discover ways to get pithy and succinct.

For now, though, I’m putting it all out here so you can take a look and decide for yourself.

- What about these ideas do you find useful?

- What would you like to understand better?

- What would help you put these ideas to work in your own business?

Please let me know – either by email, in our Meeting Success Community, or in the comments below. It’s our goal to share more of these models in the next year and your feedback will inform how we go about that.