Battle Axes to Boardrooms: A Discussion with Wilbert Van Vree

Meetings, Manners, and Civilization: The Development of Modern Meeting Behaviour, written by sociologist and meeting expert Wilbert Van Vree, was originally published in 1999, but I just finished it this March. Of the five meeting books I read this spring, this was by far the most thought-provoking, so I asked Dr. Van Vree if he’d be willing to discuss it with us here on the Lucid blog. He agreed!

The Premise:

Meeting Behavior Reveals the Progress of Civilization

About the book from the author’s website:

This is the first account of how meeting rules and behavior have developed. It takes an historical approach, from medieval meetings to meetings of the future, and provides a volume of comparative research on the development of meeting behavior; that is, human behavior during councils, assemblies, parliaments, business conferences, and other meetings (both formal and informal), to discuss and arrange a common future.

Gathering together to talk and argue about the communal future has become an increasingly important means of social integration. This study argues that, as a means of distinction for the elite, the stylization of meetings has replaced the stylization of eating and drinking. The restraint of physical violence was the “sine qua non” of meetings, and the long-term development of meetings coincides with the organization of violence within basic entities, tribes, villages, towns, nation states and confederations, which are, in effect, “meeting units”. The book seeks to provide a picture of how meeting rules and behaviour have changed over time, and answer the question of why people hold meetings.

Timeline of Events from the Book

As a product of the U.S. public education system, I found the stories used to illustrate different meeting cultures fascinating. I learned so much history I had no idea about! This timeline includes a few highlights.

Click the arrows to the right below or scroll on the timeline at the bottom to read them all.

Interview with Wilbert Van Vree

What inspired you to focus your studies on meetings?

At the outset, my interest in meetings was purely scientific. As a PhD student I was looking for a ‘strategic’ research theme that could teach me as much as possible about many people and long term trends in ‘the society of individuals’ (Norbert Elias). It was the work of the sociologist Norbert Elias that, first and foremost, got me going in researching the social genesis of meetings and meeting behavior. In his classic book The Civilizing Process, Elias showed how the transition of the leading classes from warriors into courtiers during the formation of European states, went hand in hand with the ‘civilization’ of dominant behavior standards.

At the outset, my interest in meetings was purely scientific. As a PhD student I was looking for a ‘strategic’ research theme that could teach me as much as possible about many people and long term trends in ‘the society of individuals’ (Norbert Elias). It was the work of the sociologist Norbert Elias that, first and foremost, got me going in researching the social genesis of meetings and meeting behavior. In his classic book The Civilizing Process, Elias showed how the transition of the leading classes from warriors into courtiers during the formation of European states, went hand in hand with the ‘civilization’ of dominant behavior standards.

Curious about what happened after the historical moment Elias stopped his research (ca. 1800AD), I realized that the most powerful people on earth have gradually altered from being courtiers and entrepreneurs to becoming professional meeting-holders and chairpersons. They developed the models for meetings to which an increasing number of people adhere. This is illustrated by the titles of address of the contemporary elites, such as president, vice-president, chairman, general secretary, presiding officer and congressman. These titles point to functions fulfilled in meetings. The leading classes developed the models for meetings that run our world. Attending and chairing meetings became a central and powerful human activity. This was enough reason to intensify my enquiry on the genesis of modern meeting behavior.

What happened after you published your book?

How has it informed your career?

After my book was published a whole bunch of Dutch journalists interviewed me for journals, television and radio. So, I became ‘famous’ as meeting expert in the Netherlands!

After my book was published a whole bunch of Dutch journalists interviewed me for journals, television and radio. So, I became ‘famous’ as meeting expert in the Netherlands!

At that time I still preferred to go on working at the university, but universities, especially the social sciences, found themselves in a difficult financial situation and offered very little jobs. I could have waited for some permanent employment, but decided to start my own consultancy after the Dutch Association of Board members and supervisory Board members asked me to conduct meeting workshops with their members. From them I learned a lot about current meeting practices and problems. My career as a meeting consultant and trainer had started.

Most existing training courses on meeting were (and are) predominantly psychologically oriented and do not pay much attention to the meeting culture and networks that constitute organizations. I focused on this aspect, specializing in researching and changing meeting cultures of many different organizations, including local political councils.

The Inquisition?

![]() You talk in the book about how new ways of meeting have a “civilizing” effect on the surrounding culture. I was surprised to see the Inquisition listed as an example of a more civilized approach to justice, and was of course enthralled by the descriptions of grisly medieval approaches to finding justice in circumstances “where the truth is unknowable and not knowing intolerable.” Can you talk a bit about that? Such a fascinating story and not at all how I thought of the inquisition before!

You talk in the book about how new ways of meeting have a “civilizing” effect on the surrounding culture. I was surprised to see the Inquisition listed as an example of a more civilized approach to justice, and was of course enthralled by the descriptions of grisly medieval approaches to finding justice in circumstances “where the truth is unknowable and not knowing intolerable.” Can you talk a bit about that? Such a fascinating story and not at all how I thought of the inquisition before!

Judicial arguments, which took the form of the swearing of an oath, the calling of compurgators (sworn witnesses to the innocence or good character of an accused person), and the performing of a ritual of divine judgement, were characteristic of the administration of justice in the Middle Ages. The latter involved trials by water and fire and man-to-man combat, which gave priests and warriors an opportunity to dominate the farming population. The leaders of the courts of justice, priests, royal officials, and lords, decided about the healing process of injuries resulting from trial by fire, about the sinking of an accused, and about the victor of a duel.

Judicial arguments, which took the form of the swearing of an oath, the calling of compurgators (sworn witnesses to the innocence or good character of an accused person), and the performing of a ritual of divine judgement, were characteristic of the administration of justice in the Middle Ages. The latter involved trials by water and fire and man-to-man combat, which gave priests and warriors an opportunity to dominate the farming population. The leaders of the courts of justice, priests, royal officials, and lords, decided about the healing process of injuries resulting from trial by fire, about the sinking of an accused, and about the victor of a duel.

At the start of the thirteenth century, a power shift occurred in the church, favoring those groups who were strictly opposed to the utilization of divine judgements. Building upon the remains of the Roman Empire, the church developed into an increasingly larger and more centralized organization with far-reaching influence. This organization made it possible to implement centrally issued regulations. The church developed procedures on the basis of Roman law which replaced divine judgements.

These procedures commenced with a written declaration, signed by the complainant. The two parties were no longer set against each other to duel and, from the thirteenth century, neither were divine judgements sought. Ecclesiastical administration of justice, like Roman law, focused upon confession of guilt and demanded other methods, such as the examination of suspects and witnesses, which were applied in doubtful cases instead of duels and torturous divine judgements. This was known as the Inquisition. In the end, the judge came to a verdict based on the guidelines of Roman and canonical law, which was drawn up in ecumenical councils and regional synods. With the ongoing centralizing and monopolizing of organized physical force and taxation, many procedures of ecclesiastical jurisdiction were adopted, and further developed, by royal and secular courts of law.

Controlling Behavior in Meetings

Your investigation into meeting rules and manners over time shows that people have always struggled to regulate group dysfunctions—things like personal attacks and disruptive behavior–and that the way we enforce these group norms at different points in time reveals a lot about how power and violence work in that society. So for example, violent repression was common early on. This gradually gave way to fines, shunning, and less lethal forms of control. Today, we ask those who can’t conform to please step outside.

Your investigation into meeting rules and manners over time shows that people have always struggled to regulate group dysfunctions—things like personal attacks and disruptive behavior–and that the way we enforce these group norms at different points in time reveals a lot about how power and violence work in that society. So for example, violent repression was common early on. This gradually gave way to fines, shunning, and less lethal forms of control. Today, we ask those who can’t conform to please step outside.

What other big themes struck you as human constants; as challenges we’ve always had in meetings and probably always will?

One big issue is the development of adequate language to talk and decide about ever larger groups of people. This is a permanent challenge. You need more exact facts and more embracing concepts to make decisions realistic and executable.

One big issue is the development of adequate language to talk and decide about ever larger groups of people. This is a permanent challenge. You need more exact facts and more embracing concepts to make decisions realistic and executable.

Are there other major thematic shifts in meeting behavior people should know about, beyond the shift from control using violence to control through social pressure?

Are there other major thematic shifts in meeting behavior people should know about, beyond the shift from control using violence to control through social pressure?

First, the shift from using violence to control through social pressure implies an increase of self-regulation and emotion management. ‘Meetingizating’ of society means that its members have to control their emotions more constantly and smoother within (and outside) meetings. The management of turn-taking in meetings is then often guarded by a chairperson who embodies the social control to control oneself. Generally spoken one could say that the extent to which a chairperson has to take action–and in what way–to keep order follows the fluctuations in power balances between people (and the group size). The smaller the power differences (and the group size) the smoother and more flexible the chairperson’s actions can be.

First, the shift from using violence to control through social pressure implies an increase of self-regulation and emotion management. ‘Meetingizating’ of society means that its members have to control their emotions more constantly and smoother within (and outside) meetings. The management of turn-taking in meetings is then often guarded by a chairperson who embodies the social control to control oneself. Generally spoken one could say that the extent to which a chairperson has to take action–and in what way–to keep order follows the fluctuations in power balances between people (and the group size). The smaller the power differences (and the group size) the smoother and more flexible the chairperson’s actions can be.

Chairing Modern Meetings

The advice for meeting leaders today focuses less on how to execute a series of meeting rules, and more on how to manage the flow of dialogue and feelings in a room. The implication is that to run a successful meeting, a leader can’t just follow a guide. They need to acquire some of the skills of the psychologist, the sociologist, the politician, and the therapist on top of their business or domain expertise. Is this asking too much?

The advice for meeting leaders today focuses less on how to execute a series of meeting rules, and more on how to manage the flow of dialogue and feelings in a room. The implication is that to run a successful meeting, a leader can’t just follow a guide. They need to acquire some of the skills of the psychologist, the sociologist, the politician, and the therapist on top of their business or domain expertise. Is this asking too much?

Chairing actual meetings is not easy, indeed. A chairperson must be a jack-of-all-trades. However, nobody expects a chairperson to be an expert in all of the possible skills and qualifications. People often achieve leading positions in professional organizations for other reasons (e.g. good salesperson) than having the best chairperson’s qualifications. This could be a problem and in many cases it is. Luckily one can learn to better chair, especially by doing it, by training and getting feedback.

Chairing actual meetings is not easy, indeed. A chairperson must be a jack-of-all-trades. However, nobody expects a chairperson to be an expert in all of the possible skills and qualifications. People often achieve leading positions in professional organizations for other reasons (e.g. good salesperson) than having the best chairperson’s qualifications. This could be a problem and in many cases it is. Luckily one can learn to better chair, especially by doing it, by training and getting feedback.

A Regression in Civility?

There is a persistent theme of increasing self-regulation throughout the development of meeting manners. Over time, it became increasingly unacceptable to impose one’s personal feelings on a group. Those who couldn’t self-regulate lost access to the conversation.

There is a persistent theme of increasing self-regulation throughout the development of meeting manners. Over time, it became increasingly unacceptable to impose one’s personal feelings on a group. Those who couldn’t self-regulate lost access to the conversation.

With the advent of social media, we’re seeing a reversal of this trend. People who disrupt meetings and demand their feelings be addressed are now gaining admittance to those meetings and impacting policy. How do you make sense of this in the scope of overall societal evolution? Do you think it’s a temporary reversion, or are we facing a more serious threat to the future of civil discourse?

I don’t know whether disrupting meetings and people demanding their feelings be addressed represent a wider trend and, if so whether we are dealing with a limited and temporary and or an all-embracing and long-lasting reversal. It is a complicated question.

I don’t know whether disrupting meetings and people demanding their feelings be addressed represent a wider trend and, if so whether we are dealing with a limited and temporary and or an all-embracing and long-lasting reversal. It is a complicated question.

Some preliminary remarks: Civilization and de-civilization trends are always present in society, but not equally strong and widespread; sometimes the first one is more dominant, sometimes the latter for reasons we do not fully understand yet, I think. But I am quite sure that social development and civilization are non-linear processes.

Looser and smoother behavior may be an expression of a long-term process which results in forms of conduct becoming less formal. This process, referred to as ‘informalization’ and ‘emancipation of the emotions’, has been characterized by the sociologist Cas Wouters as follows: “In the status competition, the control of emotions and self-knowledge acquired a heavier influence in respect to other criteria such as background, education, profession, and income. The fine line between forms of conduct (…) were made greater: the number of acceptable and respected behavioural and emotional variations and nuances increased between the boundaries of continuing and shutting up, and between the extremes of being too direct (rude) and too cautious (shy)”.

The advent of social media gave voice to layers of the population that were thus far excluded from power and the dominant culture and are learning by trial and error and sometimes force to behave in a more civilized way. In that case we might observe a temporarily and limited reversal of civilized discourse ending up in a new wave of informalization.

But I am not quite sure that this is the case at the moment. The rise of less civilized behavior may also be a more serious threat to the future of civil discourse as it is an expression of decreasing integration and increasing power differences, whereby conflicts between people are intensifying. Whether this is really going on, is still hard to say. We shall see what the future brings us.

When social differentiation and integration at global level go on and humankind will not be destroyed by nuclear bombs or meteorite rains, it is to be expected that human behavior further develops in the direction of more civilization (varieties).

But whether this will actually happen I don’t know. Nobody knows. We can only say things like: when certain processes (differentiation, integration) continue there is a good chance that other processes (civilization) will go on too.

What’s next for meetings?

Of course, new communication possibilities (internet, e-mail, mobile telephone and suchlike) are heavily influencing our meeting behavior. Physical gathering is not necessary anymore for group talking and deciding about the common future. In a process of trial and error we are inventing new meeting manners, tools and methods. We see a rapid differentiation of meeting behavior these days resulting in less contrasts and more varieties.

Of course, new communication possibilities (internet, e-mail, mobile telephone and suchlike) are heavily influencing our meeting behavior. Physical gathering is not necessary anymore for group talking and deciding about the common future. In a process of trial and error we are inventing new meeting manners, tools and methods. We see a rapid differentiation of meeting behavior these days resulting in less contrasts and more varieties.

I am also interested in the development of democratic meeting manners. Democracy is under pressure and so is the corresponding meeting behavior. If we don’t renew and upgrade the public, democratic ways and styles of holding meetings in time and motivate new generations to participate in political processes, there is a good chance that the more efficient but less democratic meeting manners of hierarchical organizations and authoritarian regimes will make up the dominant standard. We’ll end up as groups of selected citizens cheering on the great leaders.

At the moment I am visiting and studying meeting manners and mores of the national parliaments of the EU.

When you advise people who come to you for help fixing their “bad meetings”, where do you start? What are they key practices you think every modern organization should adopt and why?

I usually start at the top of an organization and then go down to spot the dominant meeting model of the organization. After observing and analyzing the meeting customs and automatisms of an organization I am able to formulate a plan of action. Part of such a plan is a short presentation about the possibilities and necessities of renewing meeting rules and practices of the organization. This wake-up call is followed by specific workshops with all the people who regularly chair meetings in the organization. Together we select new rules of the game and practice some of them in role-play games.

I usually start at the top of an organization and then go down to spot the dominant meeting model of the organization. After observing and analyzing the meeting customs and automatisms of an organization I am able to formulate a plan of action. Part of such a plan is a short presentation about the possibilities and necessities of renewing meeting rules and practices of the organization. This wake-up call is followed by specific workshops with all the people who regularly chair meetings in the organization. Together we select new rules of the game and practice some of them in role-play games.

What ideas and practices an organization should adopt depends on the status quo. First, everyone needs to examine carefully whether a intended meeting or your attendance there is really necessary. Then, important things are: starting and finishing in time, making agendas and preparing for meetings, limiting minutes to action and decision lists, appointing capable chairpersons (not necessarily the leading managers), making an adequate power and task-division: everybody is owner of his or her agenda item, whereby the rest of the group is adviser and consultant.

I wrote a practical guide to meetings in Dutch, which I use in my workshops and projects. I probably should translate it in English. I’ll send you a Dutch copy.

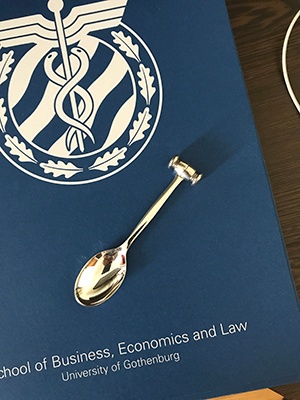

What would it cost to get a collection of your meeting gavels, including 5 of the spoons and one of everything else, shipped to Portland, OR USA 97201?

All our gavels are handmade and specially designed, produced by an artisan…

All our gavels are handmade and specially designed, produced by an artisan…

I have one of the spoon gavels here on my desk, the latest evolution in the long civilizing process taking meetings from the battle axe to the board room.

I have one of the spoon gavels here on my desk, the latest evolution in the long civilizing process taking meetings from the battle axe to the board room.

I want to thank Dr. Van Vree for his work and for spending time to share it all with us here. If you’d like to leave questions or comments for Dr. Van Vree, I’ll happily pass those along.

One final bonus: I have no idea what they’re saying in this video from Wilbert’s website, but I had to share it anyway. How awful and wonderful is this?!