Meeting Design: How to Create Standard Agendas for Your Business

Are successful meetings what your company sells?

Is your non-profit’s mission to help others run more effective meetings?

Unless you are a professional facilitator or a meeting software company, the answer is probably “No.”

Do you need the meetings you lead to succeed? To help you win sales of the product you sell, and influence those who can advance your mission?

If you care about business effectiveness, then the answer is “Yes”.

You need meetings to function well, but the meeting itself is a means to an end; not an important product of your business.

To ensure important meetings get results, organizations with a high level of meeting performance maturity rely on a set of standard agendas.

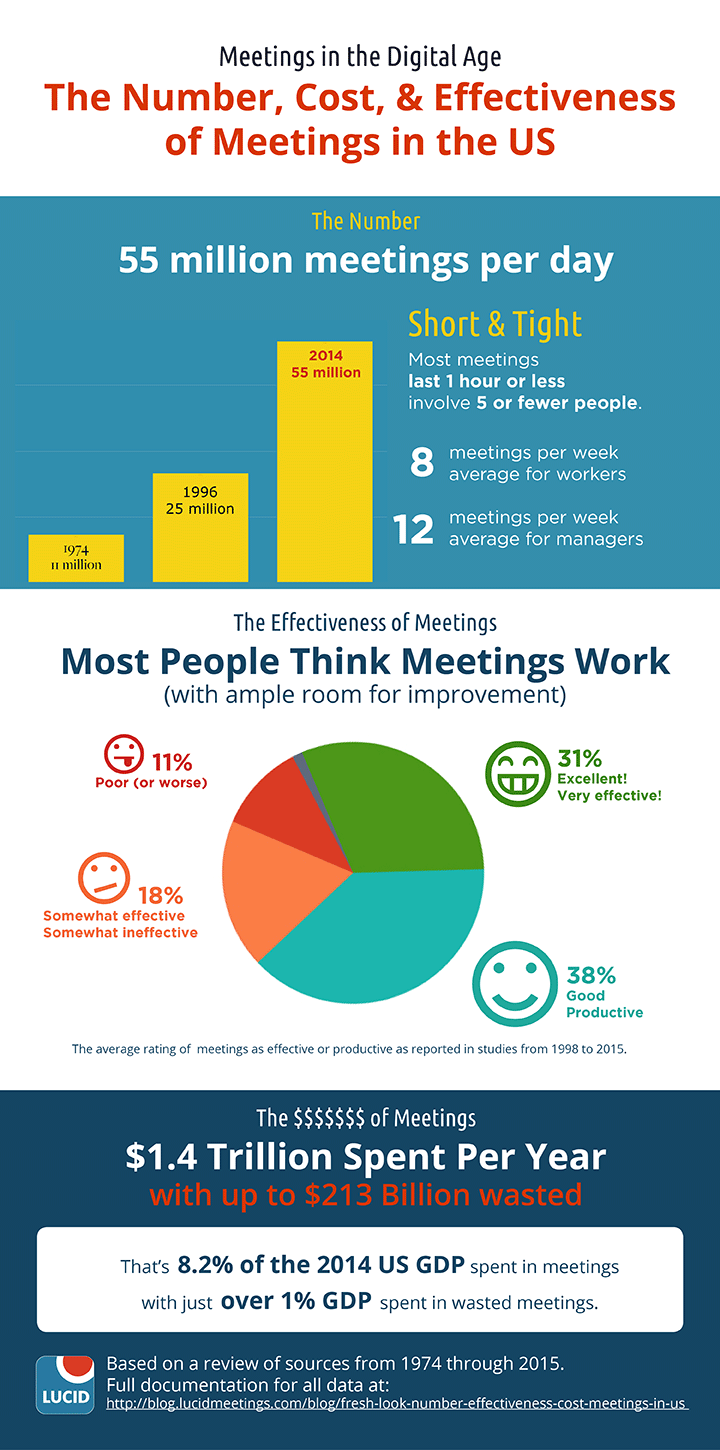

The Case for Standard Agendas

Using the same agenda discourages reinventing the wheel; once you have an agenda that works, stick to it. Plus, it also helps keep the meeting consistent.

Gino Wickman, Traction

Standard agendas provide an outline for running a specific type of meeting, so that when people need to run that kind of meeting, they don’t have to start from scratch.

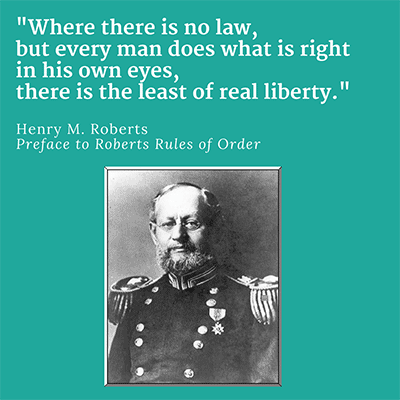

Henry M. Roberts included one of the first well-known standard agendas in the now ubiquitous Robert’s Rules of Order. Known as the “Standard Order of Business”, it gives board and committee leaders an example of how they can structure an orderly meeting.

Roberts created his infamous rules after an abolitionist’s meeting at his church erupted into open conflict. He was determined to help his countrymen engage in civil dialogue so they could work through their differences and avoid violence. Published in 1876, Robert’s Rules came too late to prevent the US Civil War, but has since been used by millions to manage heated debate and resolve differences.

Most of us aren’t facing a crisis of liberty, but we do wrestle with crises of waste, ineffectiveness, disengagement and mistrust, so we seek standard agenda structures designed to combat these problems.

In the Secrets of Facilitation, Michael Wilkinson presents several standard agendas that professional facilitators use as a starting place when planning a meeting for a client.

To maximize their effectiveness, SMART facilitators draw from a set of standard agendas that they can customize for a specific situation. Standard agendas have several advantages:

- They reduce the amount of time needed to prepare for a session by giving you a starting point.

- They help ensure that you do not miss a critical step.

- They provide consistency from one assignment to another and from one facilitator to another.

Michael Wilkinson in The Secrets of Facilitation, Second Edition

The quotes above comes from full-length books, and each of these books go into great detail about how to win with standard agendas.

To get the benefits of a standard agenda mentioned above – saved time, fewer errors, consistency from meeting to meeting, no time wasted reinventing meetings when you should be focused on your core business – the people in your organization will also need more than just a bulleted list outline. But it’s unrealistic to expect everyone to read a detailed book on meetings.

At Lucid, we do in fact sell successful meetings (in case you wondered :). When we provide standard agendas, we also include information that explains and supports that agenda in a comprehensive Meeting Template, and we call the work required to create a template Meeting Design.

Today’s post will describe how you can go about creating useful meeting templates for your business. At the end, you’ll find a link to download the worksheet we use to design our new meeting templates.

Contents

Defining Meeting Design

Meeting Design is the practice of creating a standard approach to a specific kind of meeting that includes a draft agenda and explains how to achieve the desired meeting outcomes.

Meeting design is a focused form of process design, based on these tenets.

- Successful meetings are a keystone habit, with broad implications on organizational culture and effectiveness.

- Successful meetings happen by design; success is not the natural outcome of unstructured meetings or meetings led by untrained people.

- Successful meetings come in many forms; success relies on applying good practices appropriately, as there are no “best practices” that suit every situation. If you’re familiar with the Cynefin framework, you’ll recognize that organizational communication happens in either complex, or at best, complicated settings. It’s never simple.

The Anatomy of a Meeting Template

At a minimum, a meeting template MUST have useable drafts of:

- The meeting purpose and expected outcome(s)

- The agenda

A meeting template SHOULD also instruct the meeting leader on:

- How to prepare for the meeting

- Who to invite (based on roles & responsibilities)

- The process for leading each part of the meeting

- How to follow-up after the meeting

A meeting design MAY also include:

- Example instructions to be sent to participants on how to prepare for meeting

- Detailed scripts that give the meeting leader examples of exactly what they might say or do at key points in the meeting

- Example reports or documentation expected as an outcome of the meeting

- Recommended ways to adapt the meeting to meet special needs or circumstances.

The Agenda vs. The Process

What exactly is an agenda anyway?

If you’d asked me this 5 years ago, I would have thought it a silly question. An agenda is simply a list of topics to be discussed in the meeting, right?

Since then, I’ve seen a lot of things called agendas, and they’re all over the map. Content might include:

- Subjects to discuss

eg. 1. Marketing, 2. Finance, 3. Sales, etc. - Process steps for discussing a single topic

e.g., 1. Introductions, 2. Brainstorm, 3. Sort ideas, 4. Vote - A mix of the two

e.g., 1. Announcements, 2. Review Finances, 3. Review Issues, 4. Real-Time Agenda(whaa?), 5. Next Steps - Detailed documents with attached reports, speaker bios, timing requirements, and more.

They come in all kinds of formats, from bulleted lists to multi-column tables to full-on booklets.

Then there are the un-conferences and meetings like them where attendees propose the topics for discussion when they walk in the door. The leaders tell everyone that there’s no set agenda; they’ll create the agenda together at the meeting.

Yet even in these no-agenda meetings, the organizer absolutely sends pre-work for participants and follows a specific process. Agenda-free in this case does not mean unstructured, unprepared, or winging it.

The truth is there are a lot of good ways to structure a meeting and put together a meeting agenda.

So what should an agenda contain?

Roger Shwarz says it well:

An effective agenda sets clear expectations for what needs to occur before and during a meeting.

In other words, a good agenda contains information that helps people prepare for the meeting and understand where they are in the process during the meeting.

Here’s the definition we use when writing meeting templates:

The agenda is the version of the meeting plan you share with attendees.

It may include specific topics for discussion, should include any required pre-reading, and it may explain the process you’ll use at a very high level. The agenda is not, however, the place to go into all the details about how someone should lead the conversation.

If you’ve never seen or used a detailed facilitator’s guide, this may be a surprise. Your past experience led you to believe that putting together a bulleted list was really all there was to planning a meeting.

The big news here:

Good meetings run according to a more thoughtful and detailed plan than we see on the agenda.

Tip of the iceberg, my friends.

Guiding Principles for Meeting Designers

As you get started, it’s important to remember that your meetings don’t have to look like anyone else’s. Meetings are a tool you use to achieve your unique goals, and as such, each template should be shaped to fit your culture and needs.

There are a lot of proven and useful good practices you can and should build on, adapting them with the following guidelines in mind.

Know your audience.

Experience and Institutional Memory:

Is your organization full of seasoned communicators who know your business well? Or do you work with lots of inexperienced people and high turnover?

Those with less institutional knowledge and meeting leadership experience often benefit from more detailed instructions.

Language Formality:

Are you designing a template for the Board? Do you work in a highly regulated industry with compliance requirements? Is your meeting designed to avert certain doom?

If so, the informal language of a team standup or creative brainstorming session isn’t inappropriate.

Conversely, any team that runs staff meetings according to Commander Robert’s Standard Order of Business has gone off the rails.

Stay focused on purpose.

Look too closely at any meeting, and you start to see all the little things you can improve.

Meetings can alway be more fun, more efficient, more human, more clever. But in that quest for more better, it’s really easy to find the focus shifting from what the meeting needs to accomplish towards controlling people’s behavior and creating a memorable experience.

Facilitation is the practice of making the process easier. Meeting designers must think like facilitators. The goal of meeting design is to make people’s jobs better by giving them a way to easily achieve meeting goals – it is not about control.

A design that stays focused on making it easy for someone to get the result they need becomes a tool they will use.

Reduce risk.

Keep it as simple as possible, but no simpler.

Always provide detailed scripts and sample documents any time getting it “right” really matters.

For example, many project meeting templates will include examples of the standard forms and reports reviewed in those meetings. And committees and board meetings often start with an official scripted statement concerning IP policy or conduct rules.

Try to provide additional examples and tips when this will save the meeting leader time.

For instance, if your template says the group should write down next steps, provide an example of what these might look like so the group can focus on figuring out what those next steps should be rather than worrying about what format to write them in.

Treat meeting templates as living documents.

Plan to refine each meeting template over time. As the organization’s needs and goals change, the tools in use need to change too. Fix any meeting that’s obviously broken right away, and plan to review all your regular meetings every 6 months or so to make sure they still serve you.

How to Create a New Meeting Template Step-by-Step

Meeting design is a creative endeavor, which means we usually start with rough ideas that get reworked, edited, re-ordered, ditched and/or polished as we go.

The order of the steps below helps a designer focus first on what constitutes a successful meeting before diving into the process details.

This process and the worksheet that goes with it are meant for designers building day-to-day business meeting templates. If you want to learn how to design workshops and retreats, check out the resources below.

1. Give your template a name.

Yes, you’ll probably change it later. That’s ok.

2. Define the purpose, desired outcomes, and expected duration.

Questions to Answer:

- About how long do you expect people will spend in this meeting?

- Why run this meeting? What’s the meeting’s purpose?

- What specifically will you get at the end of the meeting?

On this last one, here are three useful frameworks for thinking through desired outcomes:

1. Fill in the blank:

Once we have _______________ , the meeting is over.

examples: a decision, clear next steps, a list of issues to resolve, a plan

See Should you cancel your next meeting?

2. Rational Aim & Experiential Aim

I learned this from Jo Nelson at ICA Associates during a session on designing workshops. She coaches facilitators to think through two kinds of outcomes.

- Rational Aim: What does the group need to know by the end of the sesion?

- Experiential Aim: Who do we need to be?

Check out this example workshop design by Martin Gilbraith showing these outcomes at the top.

3. Hand, Head, and Heart

This approach from Leadership Strategies is my favorite.

When the meeting is over, what will we walk away with?

In our hands: What are the literal take-aways?

In our heads: What new shared knowledge will we create?

In our hearts: What beliefs and feelings will we have?

3. Define when to use this template.

Question to Answer:

- In what situations or contexts would someone run this meeting?

For example, is the meeting meant for internal teams, or for use with clients? Is it part of a larger series of meetings? Is it meant to be held once, or something teams run regularly? Are there special circumstances that create the need for this meeting?

4. Define who to invite.

Questions to consider:

- How many people can effectively participate in a meeting like this?

Some processes fall apart with more than 7 people, while others work best with 15 or more. - What perspectives or roles need to be represented in this meeting to achieve the desired outcome?

Some meetings include only decision makers and responsible parties. Others try to include people with varied experiences and roles to broaden the input. - What perspectives will not contribute to, or could distract from, the desired outcome?

- Does the meeting take shortcuts based on the assumption of shared context? If so, what is that context?

A simple example: if you assume everyone knows each other, you can skip introductions.

5. Do your homework.

I recommend doing the homework after clarifying the desired outcomes and audiences as a way to save a lot of study time. There are lots of good ways to run meetings, some of which your organization may already be using.

But a meeting isn’t good simply because we enjoyed attending it; a meeting is good when it achieves a meaningful organizational outcome. When you start with clarity about the desired outcomes, you can be more objective about whether the process you’re looking at will do the trick.

Start with what people are already doing.

If there are people running this meeting in your organization today, observe how it works. Hopefully you’ll discover they’re brilliant, and you just need to write down what they do to make that know-how transferable to others.

Questions to consider:

- Are the existing meetings achieving the intended outcome?

- If YES, can you document the process so that other people can achieve these results too?

- If NO, are the existing meetings achieving a different but useful outcome?

- YES: Rethink your starting hypothesis. You may have misunderstood the point of this meeting, or may need to add what’s working now to the other goals in your design.

- NO: Ouch. If that’s the case…

Get examples of good practice from the wider world.

First, start with a solid agenda framework to ensure you have the basics covered.

After that, here’s where I find many of the examples I use.

- Internet searches

You can find lots of example agendas online. These tend to just be simple outlines, though, and rarely include much information about the situation they’re designed to address. - Books about meeting facilitation

Several facilitation books include sample agendas for core meeting types, things like “Decision Making Meeting” or “Issue Resolution”. These processes are super solid, and may be easily adapted to a more specific template such as a “Candidate Selection Meeting” or “Change Request Review Meeting”. See the resources list below for the ones I reference most often. - Business Books

Many books that discuss how to do a specific job will also talk about how to run the meetings commonly held as part of that job. Business leadership books may describe how to approach strategic planning and operational review meetings. Books for project managers describe how to run a project status update or an after-action review. HR will describe how to lead interviews, and employee on-boarding. Sales people can’t stop talking about how to make meetings work, because getting and rocking meetings is how they make their living.

Pro tip: people who write books about meetings are often thrilled to work with new clients to help them design meetings. If you get stuck, it never hurts to ask for help!

6. Revisit your assumptions.

Context, Purpose, Duration, Who to Invite, Desired Outcomes – does all that still look right?

At this stage, you’ll either have verified that you’re on the right track, or you’ll see that you’re trying to do too much in one meeting.

When you need to accomplish a lot in a meeting, but don’t feel you can realistically achieve it all in the allotted time, here’s what you can do.

- Split the meeting into multiple sessions.

Several sessions of 90 minutes or less, scheduled one or two days apart, often work very well. - Move work outside the meeting.

Reading reports, brainstorming ideas, and providing feedback can all happen before the meeting. - Make the meeting longer.

Beware, though, of any meeting longer than 2 hours. Long meetings need breaks and snacks. - Settle for less.

7. Draft the agenda AND process at the same time.

I recommend working these together. It’s pretty common to find you should re-arrange or combine items on an agenda, or that adding a few more steps in the agenda helps make the process easier to run.

As discussed above, the draft agenda should be the version of the meeting plan shown to attendees.

I find that less-is-more here. Too much information in the agenda often feels overwhelming, and makes the meeting look like a lot more work than it is.

8. Document how to prepare for the meeting.

Include the following for the meeting leader:

- How far in advance to schedule the meeting

- Room and/or equipment setup

- Any recommended pre-meeting conversations

- Reports or other presentations to prepare

Also add any preparation instructions that should be sent to participants in advance.

9. Define how to document and follow-up after the meeting.

Questions to consider:

- What should a report from this meeting look like?

- Who needs to see the report?

- Which business systems need to be updated with the meeting outcome? (e.g., CRMs, project records, board archives, etc.)

- How and when should any follow-up meetings be scheduled?

Hurrah! At this point, you’ve got a fully fleshed out meeting design!

The heavy lifting is behind you. Now it’s time to…

10. Test and Refine Your Design.

Personally, I like to test a meeting design I’ve written myself first. This gives me a chance to catch the really stupid errors and unworkable processes before I inflict them on someone else.

That may not be appropriate for you in your role, though. If not, enlist a willing meeting leader to test the design and observe their meeting. For internal meetings, you can often test these in the real situations where they’ll be used.

For meetings designed to include clients or other high-stakes external audiences, consider running a practice session internally first. You’ll need to do some role playing for this one, but while that can feel a bit weird, it’s not as bad as subjecting a client to a poorly thought-out process.

Don’t worry if the test meetings are a little awkward. Any new process is going to take some time before it feels comfortable. During your test, expect the awkward, but watch out for:

- Outright confusion

- Disengagement

- Signs that the conversation is making people feel unsafe

- Failures to achieve the desired objectives

These are signs that you may need to adjust your design.

I say “may” because meetings are full of people, and working with people is always complicated. There is no meeting design on the planet that can guarantee you’ll keep everyone engaged, and no process that will prevent confusion for someone who isn’t following along.

If you find that you need to stop and explain the process often, however, or that the group isn’t anywhere close to the goal, the template definitely needs more work.

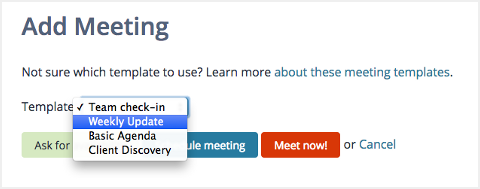

11. Publish.

If you use Lucid to manage your meetings, add your meeting designs as new meeting templates for your account. This will make them available for people in your organization when they go to schedule their next meeting.

If you don’t use Lucid, find a way to publish your template where people scheduling and running meetings will be sure to see it. Ideally, your hard work will save everyone time and improve the organization’s overall meeting results – but only if the template gets used.

For those who run most meetings face-to-face, consider printing out the template and placing copies in your meeting rooms. Adopt a “Meeting in a Box” approach, placing all the guides and setup material needed for that meeting together where leaders can put it right to use.

12. Monitor and Update Regularly.

This is that “living document” part. Pay attention to the meetings using templates to see what works well.

Always remember that no process is sacred.

A pre-defined meeting process is a tool designed to help people – not to control them. The process in and of itself is never the point; it’s useful only if it makes it easier to achieve our goals.

Change the template any time it’s not doing its job.

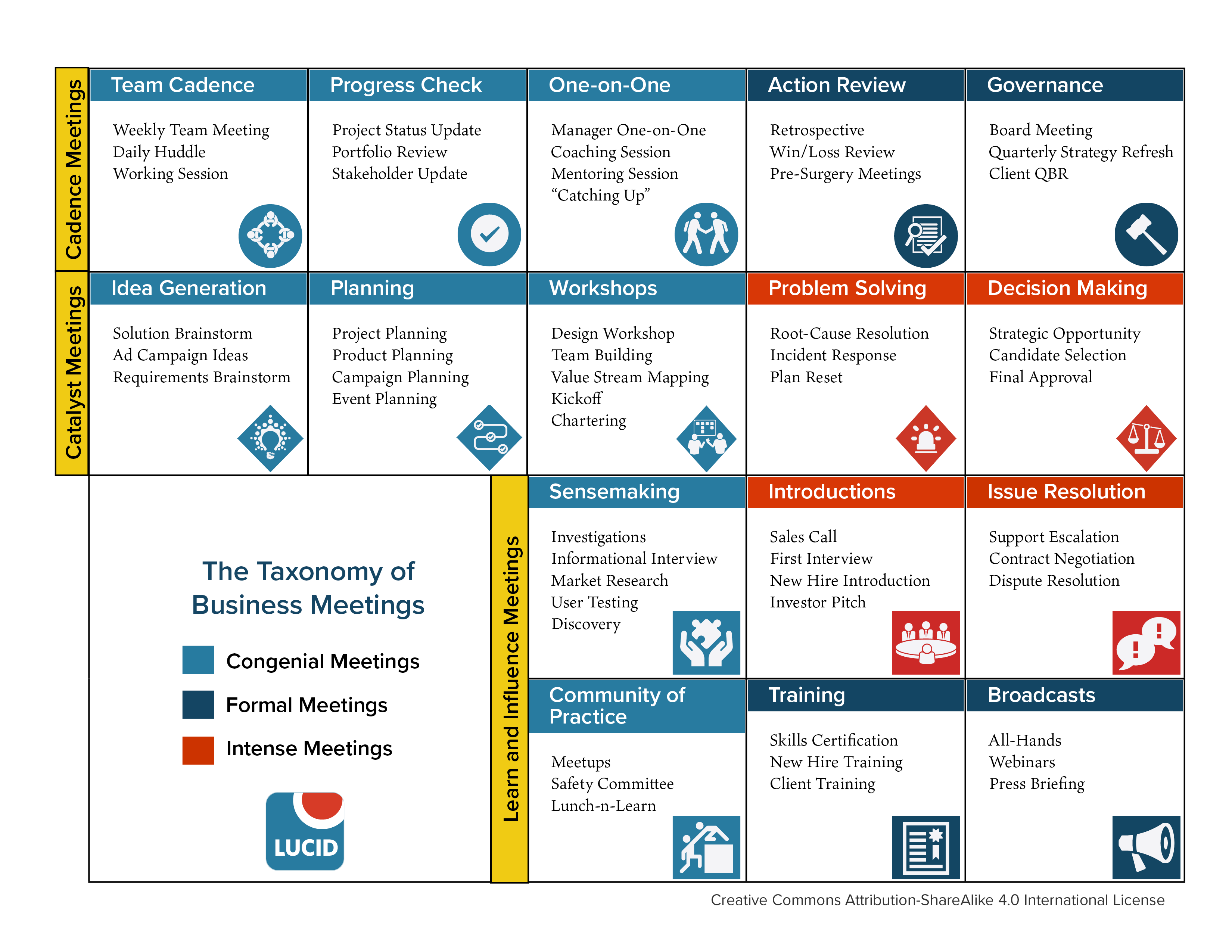

Which meetings should you design in advance?

It’s neither necessary nor a good investment of time to try and script every conversation held in your business.

We believe companies and organizations benefit when they create designs for these meetings:

The meetings that make up your regular “meeting cadence”

Meetings that happen frequently and regularly in your business should have a meeting template. This will include things like the weekly leadership team meeting, or the agile planning session at the beginning of each sprint.

Templates for these meetings benefit your company by:

- Establishing effective meetings as a keystone habit & creating a cadence of accountability

- Making an activity you do often more efficient

- Ensuring you have a process that prioritizes important decisions

- Avoiding the performance implications of decision fatigue that can happen when people have to decide what to talk about and how to talk about it several times a week

Meetings with high-stakes business outcomes

OR high-stakes social impact

There’s a good chance your organization already has draft agendas for these. Examples here include board meetings, sales calls, community meetings, and client kick-offs. If your company has any meetings in the box, they fall into this category.

The benefits here are more obvious; by failing to plan you plan to fail. Not an option for these kinds of meetings.

A few generic designs that can serve as a starting place when designing one-off meetings.

Happily, these are the “standard agendas” you’re most likely to find in a book on facilitation, as there are a number of situations common to all organizations.

A generic template describes the meeting process to use, and can be adapted to fit whatever the specific topic might be.

Examples:

- A decision-making meeting

- A crisis response

- An information gathering meeting

Bonus! The Lucid Meeting Template Gallery includes lots of free templates for generic meetings to get you started.

In Summary

- Meeting Design is the practice of creating a standard approach to a specific kind of meeting that includes a draft agenda and details how to achieve the desired meeting outcomes.

- Meeting designers create meeting templates used by their organization to run consistently effective meetings.

- There is no one-size-fits all best practice here, but there are many good practices for designers to build on.

- Here’s a worksheet you can use to get started!

As I mentioned above (Pro Tip!), most meeting professionals are happy to answer questions and provide help. After all, these are people who decided to spend their careers helping other people run meetings – of course they like to talk about what they do!

We’re happy to answer questions too, and look forward to your feedback in the comments below.

For those of you who like the idea of getting custom meeting templates for your organization, but who do not like the idea of actually designing these templates yourself, check out our Services page. We’re happy to help. After all, we’ve got a handy template we can use!

Additional Resources

These books include sample agendas and instructions for designing meetings.

- Leading Great Meetings: How to Structure Yours for Success by Richard Lent

You can see some of Rick’s meeting templates in the Lucid gallery. - The Secrets of Facilitation, Second Edition by Michael Wilkinson

- The Secrets to Masterful Meetings: Ignite a Meeting Revolution also by Michael Wilkinson.

This one is geared more towards regular business meetings, offering a condensed set of the tips in the comprehensive Secrets of Facilitation. - Facilitating with Ease! by Ingrid Bens

Ingrid also has a great series of designs specifically for consultants. You can see her template for running a group discovery meeting in our gallery.

This post is the fifth in a six-part series exploring what it takes for companies to run consistently worthwhile meetings.

- Introduction: Creating A Foundation for Changing Your Organization’s Meetings

- Meeting Strategy: Why meet? Understanding the Function of Meetings in the Collaborative Workplace

- Meeting Execution: The Underlying Structure of Meetings that Work

- Meeting Cadence: How often should you meet? Selecting the right meeting cadence for your team.

- This post! Meeting Design: How to Create Standard Agendas for Your Business

- Meeting Performance Maturity: How to evolve meeting performance across the organization