Meetings and Productivity: Driver or Drain?

Looking at the ROI (Return on Investment) of meetings provides insight into which parts of the business need to take meeting performance more seriously, and which parts are already working well.

In a recent webinar (click here to see the recording), I shared the four main areas of organizational performance that are most impacted by meetings.

Some of these, like sales and new business development, directly impact our ability to generate new top-line revenue. The ROI of training sales people to run excellent meetings is no-brainer obvious; trained sales people sell more stuff and make more money.

The ROI of improving how managers meet with employees is not quite as obvious, but it’s also not that hard to figure out.

Studies(1)(2) show a proven strong impact on employee engagement and retention when managers lead better meetings, and high employee engagement is correlated with strong organizational performance in every sector.

People who feel valued, who understand what they’re trying to achieve together, and who have a voice in the meetings where work decisions get made do better work. When you look at it that way, an investment in learning to run better manager-employee meetings makes great financial sense.

There’s one area of organizational performance where the picture isn’t so clear: productivity.

Meetings interrupt productive work, and when run poorly, meetings drain people’s energy. They also give people the information they need to keep work productive, driving decisions and mutual accountability.

Meetings both drain and drive productivity. So how do you invest wisely?

In the webinar, we looked at the question of productivity in financial terms and explored how to calculate these productivity impacts in dollars and cents. Want to learn more?

The Webinar Recording is Available!

For a more human-centered appetizer, here’s an excerpt adapted from Chapter 9 of my new book Where the Action Is: The Meetings That Make or Break Your Organization.

The Impact of Meetings on Productivity

There are many people who feel that meetings and productivity are natural enemies—that every meeting is simply a stinky, hungry lion that devours the graceful gazelle of awesomeness they would otherwise be creating.

Regardless of whether you believe meetings eat work or, rather as I do, that meetings are work, it’s useful to see what we can learn from research on productivity and the implications this has for getting to meetings with a Net Positive Impact.

Let’s start by clarifying the kind of productivity we’re discussing.

Jobs with low interdependence on other people and high predictability (so routine, repetitive, and low-skill tasks) don’t require people to maintain strong focus to stay productive.

For example, my eldest packages hummus. This involves lots of repetitive scooping and labelling. For him, an interruption is no big deal; he can easily pick back up where he left off with his vat of tasty garbanzo goo.

The productivity that meetings may jeopardize is focus time spent by individuals in creating something new. That maker time required by knowledge workers everywhere. Here’s what the research can tell us about that precious focus time.

It takes up to 25 minutes to get focused after an interruption.

Meetings are always interruptions, but they are hardly alone.

Instant messaging (chat), email, phone calls, and simply sitting in a noisy open office can also interrupt someone’s focus. In fact, while “too many meetings” always rates high on the list of interruptions people feel keep them from work, studies find that the rise in always-on communication technology is worse.

One study carried out at the Institute of Psychiatry found excessive use of technology reduced workers’ intelligence. Those distracted by incoming email and phone calls saw a 10-point decline in their IQ—more than twice that found in studies of the impact of smoking marijuana, said researchers. “‘Infomania’ worse than marijuana,” the press declared.

Even more alarming, that study was from 2005 and predates the introduction of Twitter (2006), the Facebook News Feed (2006), the iPhone (2007), and the latest always-on darling at the time of this writing, Slack (2013).

There is an unmistakable hit to productivity when people are interrupted, and if you look at the pure math of it, the situation looks dire. And yet, we’re all clearly more distracted than ever before, and still the world turns. Work gets done.

So how can this be? Distraction and interruptions are at an all-time high, and work still gets done. Does that imply that we don’t need to worry about these interruptions after all?

It turns out that humans are adaptable creatures. In studies looking at the impact of task-switching on productivity (what happens when you’re interrupted, or when you try to multi-task), researchers found that people are pretty good at compensating for interruptions. Writing email, reading reports, cooking—those of us who are interrupted frequently during these tasks compensate by typing, reading, and chopping faster than ever!

At the organizational level, your employees’ ability to compensate for interruptions may be mitigating some of the big productivity hits, but that doesn’t mean there’s no impact.

Surprisingly our results show that interrupted work is performed faster. We offer an interpretation. When people are constantly interrupted, they develop a mode of working faster (and writing less) to compensate for the time they know they will lose by being interrupted. Yet working faster with interruptions has its cost: people in the interrupted conditions experienced a higher workload, more stress, higher frustration, more time pressure, and effort. So interrupted work may be done faster, but at a price.

““The cost of interrupted work: more speed and stress.” Gloria Mark, Daniela Gudith, and Ulrich Klocke (2008).

Even though work still gets done, it’s stressing us out!

The most obvious relationship between meetings and productivity is this: Meetings can negatively impact productivity by interrupting other tasks.

But…

Meetings drive work completion.

An old adage says that a task will expand to fill the time you give it.

Creative work can always be refined. Knowledge work can always achieve a deeper level of truth. Athletes can set new records. That report can always include a shinier chart. We are never really done, so sometimes we need an external constraint to get us there.

Research into creativity and productivity found that, contrary to expectations, teams with severely restricted resources actually produced more creative work than the teams who had more time, money, and access to resources.

Constraints, it turns out, force us to figure out how to get things done.

Meetings can act as a necessary constraint.

Meetings set a deadline on the calendar when people are expected to report on progress. Just like a homework due date in school, the meeting date forces people to stop procrastinating and get stuff done.

Project managers know this pattern well, and it’s one reason the project status update is a workplace mainstay even though it is also one of the most universally loathed meetings. Many project teams see a dramatic increase of productive output the day (and night) before an important milestone.

In fact, in our Meeting Taxonomy chart, there is whole row of meeting types dedicated to Cadence meetings, all of which are in part designed to impose a useful constraint on how long a team can spend before they need to report some progress.

Meetings as deadlines work extremely well, which is one reason you can see meetings metastasize across an organization. It’s a tricky balance, but one that we need to try to get right because…

Too many meetings block the flow. So do too few.

I started this discussion of meetings and productivity by clarifying that we’re not talking about the kind of productivity that my teenager needs to achieve when packaging hummus. Instead, we’re more concerned about the impact of meetings on the productivity of modern knowledge workers and skilled professionals.

Next, I shared research that showed how interruptions like meetings could make it take longer to complete tasks like writing an email, and the time penalties paid when we task-switch. But then on the other hand, there’s nothing like a deadline to force a project into action. Anyone who’s spent any time in the business world knows that many reports are completed exactly 10 minutes before the meeting starts. Deadlines force completion.

Composing email, finishing the report: often important work, but not exactly world-changing. For truly inspiring results, organizations need highly skilled people working in the flow.

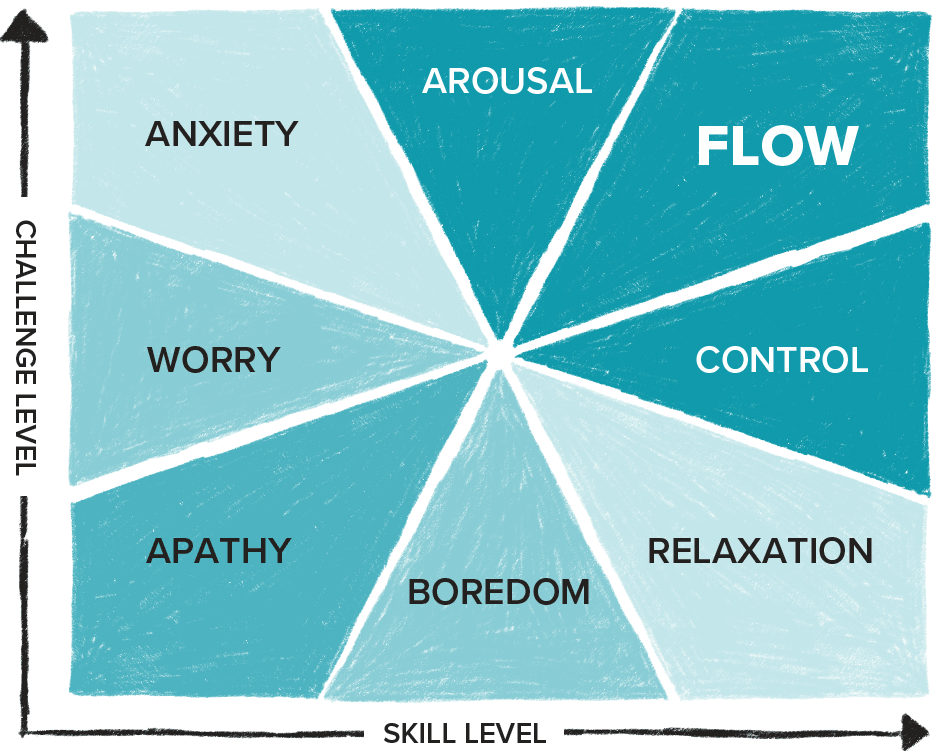

“The Flow” is the name given to a skilled individual’s peak productive state.

Great work happens when people are in the flow, a state of deep concentration and productive output that, when achieved, temporarily suspends time. Research conducted by positive psychologist Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi and his international team found there are 10 components of the flow state.

- Having a clear understanding of what you want to achieve.

- Being able to concentrate for a sustained period of time.

- Losing the feeling of consciousness of one’s self.

- Finding that time passes quickly.

- Getting direct and immediate feedback.

- Experiencing a balance between your ability levels and the challenge.

- Having a sense of personal control over the situation.

- Feeling that the activity is intrinsically rewarding.

- Lacking awareness of bodily needs.

- Being completely absorbed in the activity itself.

In the flow state model (shown below), you can see that Flow occurs when a highly skilled individual engages with a challenge that’s just at the edge of too challenging. From the list above, you can see that getting into the flow requires a big chunk of dedicated time.

People describe the flow state as a feeling of euphoria or ecstasy.

Researchers believe that’s because when people are in the flow, they focus all the brain’s available resources on a single activity and, in doing so, lose any sense of their mundane problems, the people around them, and even of their own bodies.

It is a wonderful feeling arising from a fundamental cognitive limitation: our brains can only pay attention to so much at once!

Personally, I seek the flow state whenever I can. It’s a deeply rewarding experience to engage successfully with a tough challenge. And productive! So many more pages written so much faster! That’s bank money, friends.

As a business owner, I also want to create the conditions that give my employees access to the flow, because the results that come from people working in the flow can exceed any expectations.

When people are deeply engaged and appropriately challenged by their work, they’re happier, they spontaneously put in more effort, and they continuously improve.

Workplaces optimizing for flow must make sure high-skilled employees have adequate uninterrupted time to focus. Make sure to reserve several large meeting-free blocks on the calendar to maximize the opportunity for flow.

People require uninterrupted time to achieve flow, but that is not the first item on Csíkszentmihályi’s list above.

The first item is: 1. Having a clear understanding of what you want to achieve.

This clear understanding will often emerge from a meeting.

We meet to quickly create shared perspective in a group. Shared perspective is the prerequisite to setting clear goals.

Use meetings to ensure people understand the organization’s goals.

I’ve noticed something striking about the organizations Lucid Meetings sees that have achieved a high level of meeting performance maturity. Each one of them uses some form of pervasive transparency to encourage distributed decision making.

Several companies champion open book management, giving every employee insight into the organization’s detailed financials. “Vivid visioning,” where the company vision is written as a full narrative view of the future rather than just a few pithy lines, is a common theme.

At first I thought this was a striking bit of nobility—I’d found the good guys! These folks care about all the little people!

Digging deeper, I discovered a more pragmatic reason for this extreme openness: access to information dramatically increases employee performance.

If people know the organization’s current goals, understand the longer-term vision they’re being asked to help build, and appreciate the current conditions affecting their work, they have a clear understanding of what they need to achieve. Flow becomes possible, and high-maturity meeting practices are a primary tool used to get there.

A final point about flow: uninterrupted time does not mean solitary time.

Chess players achieve flow in a match with an opponent. Musicians and dancers achieve flow during group performances. Computer programmers achieve flow when working together on solving challenging software problems.

For some work tasks, it may be in a meeting where the group achieves flow. Highly skilled business leaders meeting to respond to a strategic threat will lose track of time and forget to eat while they’re meeting “in the thick of it.”

Sometimes supporting the flow means you meet more, not less.

Text adapted from

Where the Action Is: The Meetings That Make or Break Your Organization

available on Amazon today.