Why Meeting Flow Models are the Key to Unlocking Your Team’s Meeting Success

For every significant goal your company needs to achieve, your team meets. In most companies, these meetings get very little forethought. They’re just part of what happens as you do the work.

In other companies, teams plan out the meetings they’ll use to achieve their goals. They design each meeting, just like they design the forms they use for capturing data and the reports they’ll use to measure progress.

This meeting design work is a critical but often neglected aspect of successful business process design.

Here at Lucid, we call the design of a series of meetings related to a specific business process Meeting Flow Modeling. If you’ve ever heard me talk about the three parts of an effective Meeting Operating System, you may recognize this term.

- Meeting Flow Model

- A Meeting Flow Model is a form of process documentation that highlights the main meetings used to achieve a business result.

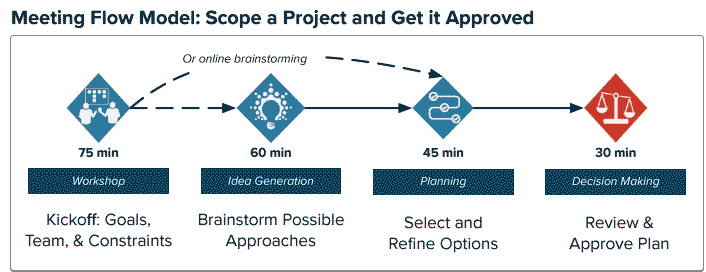

For example, here are a few of the meetings you might run when you want to scope a new project and get your plan approved.

Meeting Flow Models provide a central pillar around which you can design a process’s larger Communication Architecture.

- Communication Architecture

- The method and frequency by which information flows between people, teams, and systems in your organization.

For example, the Communication Architecture for a project team will include several meetings like the ones shown above. It will also include a project tracking system, regular email, chat communications, and other systems.

We learned the term Communication Architecture from Ben Horowitz. It’s a super handy idea that gives us all a common way to talk about and critically examine how we move information around in our businesses.

The term Meeting Flow Model and the focus on Meeting Flow Modeling as a practice is our contribution.

Our work here is inspired by the meetings we’ve observed in high-performing teams worldwide. Great teams establish a Meeting Operating System that consists of:

- Performance criteria to set shared expectations for meetings;

- Meeting Flow Models that define the timing and type of meetings teams run, and;

- Support, ensuring teams have access to resources and training needed for these meetings to succeed.

Lots and lots of people have created or attempted to create Meeting Flow Models in their businesses without the benefit of common language they can use to describe what they were doing to others.

That’s so hard! We’re giving this work a name and defining a structure so we can make meeting success easier for us all.

This article provides an introduction to the Meeting Flow Model (MFM) concept. The next article in this series introduces the practice of Meeting Flow Modeling, detailing how to create a Meeting Flow Model. Future articles will describe real Meeting Flow Models your teams can use.

What? I’m lost. Give me another example!

No problem!

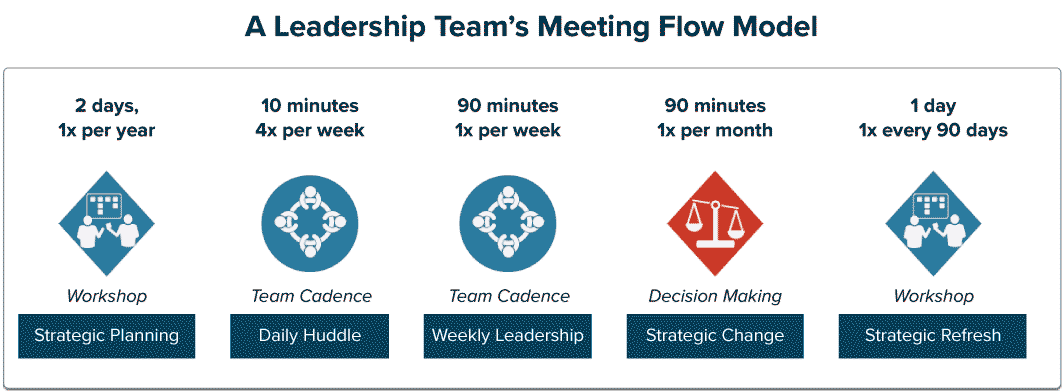

Our most popular article and template pack describes a simple MFM used by leadership teams to set organizational strategy and manage operations.

There are five meetings in this model.

You can read all about these meetings, download guidebooks for running them, and see how they work together here: The 4 Meetings That Drive Strategic Execution

Teams that define and use an MFM like this one experience these benefits.

How Team Members Benefit by Using Meeting Flow Models

Team members using a defined MFM know why they’re meeting and what to expect.

In a good way – not just in a “Yeah, I know what to expect. I expect it to be a waste of friggin’ time!” sort of way.

An MFM spells out which meetings you’ll run and when you’ll run them. This makes it possible for everyone to come prepared for those meetings. They aren’t showing up to meetings wondering why they’re there, what the purpose is, or how long they’ll have to endure before they can escape.

An MFM also makes it possible for them plan their time, because meetings aren’t just popping up higgledy piggledy on their calendars.

As our world becomes increasingly complex, an established MFM provides precious predictability.

Team members can improve their meetings.

Now that you have known meetings at known times, you can evaluate and improve those specific meetings.

Most companies occasionally ask employees what they should do to “improve meetings” in general. They get generic answers in return. Employees say everyone should use an agenda, keep meetings shorter, and prevent blowhards from hijacking the conversation. Maybe leaders should confiscate everyone’s phone. The answers aren’t necessarily wrong, but they aren’t very specific and most importantly, no one actually follows this advice.

If, on the other hand, you ask people how to make a specific meeting that has a well-defined goal better, you get answers that actually help.

Let’s take a super simple example.

Case in Point: Board Meetings

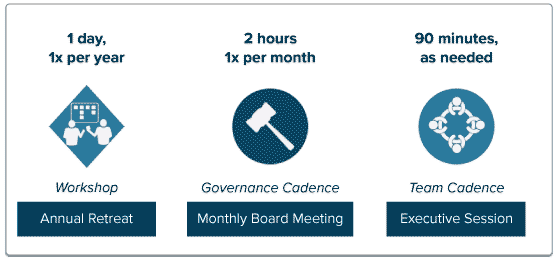

Boards run board meetings, usually monthly or quarterly. A board’s MFM looks something like this.

If those board meetings aren’t working well, they don’t have to figure out how to fix “meetings in their organization” (that general, blergh kind of problem). They talk about how to run better board meetings based on the unique needs of their organization and the people involved. Should they change the frequency? The location? Should they rotate the focus of their meetings; tackle operations one month, then strategy, then finance, perhaps?

Those are questions everyone involved can help answer and changes the group can easily implement.

Here’s another example from our own practice here at Lucid.

Case in Point: Our Daily Huddle

We use a variation of those leadership meetings above to run our business. As a small remote team, we found the Daily Huddle hard to schedule. We understand why that meeting is valuable and agreed that we needed the daily updates about what’s going on. But since we’re all working at different times, there wasn’t a good time to hold the meeting without interrupting someone’s important focus work.

So – instead of a daily meeting, we check in using our team chat every day. We accomplish the same goal in a way that works better for our team and our schedule.

Knowing how daily huddles work, how they fit into the overall communication architecture, and why teams use them let us make good decisions about how to best get that value for our team.

How Leaders Benefit by Designing Meeting Flow Models

Designing your MFM forces you to think through the Value Stream.

- Value Stream

- The sequence of activities required to deliver a specific good, service, or other form of value to the intended recipient (aka Customer).

The term Value Stream comes from the manufacturing world, where they focus intently on eliminating waste. When you’re churning out thousands of widgets, every penny saved reaps big rewards.

In knowledge work, our value streams aren’t as easily defined or tidy, but neither are we helplessly whipped by the whimsy of an unfathomable universe. There are basic steps in the creation of every knowledge product that you can anticipate in your MFM.

What can you know about your work without even looking at the specifics?

You know you need to assemble a team. You know the team needs to agree on what they’ll do. You know they’ll need a way to make sure they’re doing it. You know they’ll need to agree when they’re done. And, importantly, you know crazy unexpected things will happen that you’ll need a way to figure out.

When you design An MFM, you can’t plan for all eventualities, but you can absolutely plan for how you’ll talk through whatever eventualities come your way.

Case in Point: A Design Firm’s Project Meetings

Our friend Beatrice Briggs shared a great example from her work with a design firm. She was brought in to help the design teams run better project meetings.

The team identified big problems that were derailing their project schedules, undermining profitability, and frustrating clients. Ms. Briggs helped them address these problems by working with them to create an MFM for their client projects.

Here’s one of several examples from that work.

The designers complained that the clients weren’t always forthcoming about their publicity issues in early meetings. When these issues were revealed later, the design team had to scramble to rework their designs.

With a bit of investigation, they learned that some clients withheld information because they were afraid it would leak out. Now, after creating their MFM, designers make sure they have a confidentiality agreement that they go over with clients before asking any sensitive questions.

It turned out that other clients weren’t withholding information at all. The designers simply weren’t asking the right questions. Without a defined way to run client meetings, each designer asked the client whatever questions popped into their heads and as a result, they received wildly different answers. Now, all the designers use a standard agenda for those early meetings that makes sure they cover the key questions with every client.

Finally, while every project ran into some kind of unforeseeable obstacle along the way, the team didn’t have a standardized way of handling those changes. Today, their new MFM includes a way to run Project Change Request meetings. Designers explain how these Change Requests will work in that Kickoff, so both they and the client know right up front how they’ll work together when the unexpected inevitably pops up.

That story shows what happens when you zoom out and look at your meetings as key activities in a larger process. In the case of this design firm, they were already running all kinds of meetings in their client project work. Working to define their MFM wasn’t about adding more meetings to their schedule. It was about making sure the team was using meetings to make the process as efficient and successful as possible.

By changing the way they ran the very first meeting with the client, they were able to make every part of the project that followed a lot easier. But they wouldn’t have gotten that result if they were just trying to design a fun kickoff meeting. They got there by looking at that kickoff in the context of the rest of the process.

When we look at what high-performing teams do, we often find they meet far less than other teams because they’ve designed each of their meetings to efficiently drive work forward. When you map out the meetings in your process, you’ll often see ways you can adjust one meeting to make it more productive and thereby eliminate the need for other meetings.

How Organizations Benefit When Teams Use Meeting Flow Models

MFMs clarify your leadership training and development path.

What does it mean to be a leader in your organization? How do you identify and prepare people to move into those leadership roles?

In most companies, the answers are convoluted and involve lots of emphasis on finding people with desirable personality traits: emotional intelligence, empathy, confidence, decisiveness. Most have less clarity on what the job skills of leadership entail – even though we all know leaders typically spend between 50% and 80% of their work day in meetings.

When your organization defines your core MFMs, you’ll know exactly what leaders need to accomplish in all those meetings. You and your prospective leaders will know what they’ll be doing on the job, what success looks like, and how to achieve it.

Case in Point: Cisco’s One-on-Ones

At Cisco, they realized their approach to performance and talent management wasn’t working, so they ditched it. Instead, they began searching for the practices that made the most measurable difference to their team performance. You can read more about what they’re doing here.

Cisco discovered that when team leaders hold a weekly one-on-one with every team member, performance improves. The results were so clear that completing these one-on-ones is now a key performance metric for team leaders. It’s also made it very clear to Cisco employees: if you want to become a team leader, this is what that job involves.

Ashley Goodall, Cisco’s SVP Leadership and Team Intelligence, answers questions about their process in a regular video podcast. One director asked: “My managers say they don’t have time to check in with their team members. How and why should they find the time?” You can see his answer here starting at 2:33 – and see how confident he can be now that Cisco has this clarity.

MFMs support more accurate resource allocation and budgeting.

I mentioned above that most leaders spend 50 to 80% of their time in meetings. That’s a big range drawn from several broad studies, which means for you, it’s pretty worthless as a planning or budgeting number.

Some companies combat this by pulling calendar data to get more accurate numbers. It’s a useful way to get a sense for your meeting investment and a better-than-generic answer, but it’s still not enough for planning.

Calendar data can’t tell you how much time each person spent before the meeting preparing or after the meeting following up, so the numbers you get show just part of your total investment. It can’t tell you which part of your business each meeting supports. Finally, you can’t tell from the calendar which of those meetings were critical and which were a waste of time.

When you have defined MFMs and know what meetings people can expect to attend each week, you’ve got real numbers.

Let’s take the Cisco example again. How many people can each team leader lead? The answer is: the number of people that they can meet with every week while still getting their other work done. While that number probably varies from leader to leader, Cisco can know that it’s going to be more than 3 and probably fewer than 20 – and that tells them how many team leaders they’ll need.

At Lucid, we have MFMs for all our big client engagements. For an example, I’ve shared our work to craft an MFM for our Enterprise software pilots. With that model in place, I know how many pilot projects our company can handle at once and where we need to hire first if we want to scale up to take on more of that work.

MFMs give you a tool for designing your culture.

“At my work, we talk about culture all the time, but I’ve never known what to do about it. Now I know.”

This is one of my favorite things to hear in the feedback at the end of a workshop, because it’s so simple and so powerful. We all know that what we call organizational culture comes not from our values posters or mission statements. Culture is The Way things really work in our organization: how we talk to each other about our work, the questions we ask, what we expect from each other, how we handle failure, what we celebrate, and how we listen.

When you design your meetings, you get to design The Way each of those conversations works so that it supports the cultural values you’re hoping to see.

Case in Point: Zingerman’s

Zingerman’s, a community of food-based businesses in Michigan, was co-founded by a reformed anarchist – the kind of anarchist that believes in creating equality by building everyone up to become leaders rather than by tearing leaders down.

“Every cook can govern.”

C.L.R. James

Teams at Zingerman’s use their weekly team meeting to model these values with every employee.

Every week, the facilitator opens the meeting with an ice breaker of their choice. Everyone speaks, showing that every voice matters (and they like to have fun). The facilitator is never the manager. The week I observed a meeting at their pub, the facilitator was a waitress.

Then after the icebreaker, they all look at the scoreboard together – this great big board on the wall that includes their performance numbers: income, expenses, satisfaction scores. To make sure every employee is ready to participate in this part of the meeting, they all learn how to read a balance sheet during onboarding.

With the numbers on the board in front of them, team members take turns reporting on the past week’s performance – and the people doing the reporting are those closest to that part of the work. I watched a dishwasher who was still in high school report the maintenance expenses for the past week. After looking at the numbers, they celebrate customer notes about excellent service with applause. Then they discuss opportunities for improvement, which anyone can suggest.

Finally, before they leave they review action items and share appreciations, where everyone has an opportunity to express gratitude for something good another employee did in the past week. Appreciations help them end on a positive note and reinforce what “good” means in their culture.

Zingerman’s employee retention is astoundingly high for their industry, business is good, and perhaps most importantly, as one of their waiter’s told me:

“My friends say I’m a nicer person now. I like that.”

The Zingerman’s weekly meeting covers the same ground that every team’s weekly cadence meeting covers. They talk about what they did last week, their plans for the week ahead, and they share both insights and problems. Sounds like a super typical weekly team meeting – or at least it would be, if they didn’t also use that precious time to model and reinforce their desired corporate culture.

Compare that to the situation in most companies.

Most companies leave the decisions about how and when to meet up to every individual manager. It’s what we call Level 1 performance, and it’s by far the most common approach.

But what happens when the executive team decides to push a culture change initiative–DE&I, innovation, or transparency, perhaps? They have to assemble big change management teams and run a culture change initiative that they’ll measure using employee surveys. These programs usually fail to consider how this initiative should change the way teams meet every week (which is where all that culture is happening on the ground) and unsurprisingly, have a notoriously low success rate.

By contrast, when teams with a defined MFM like Zingerman’s want to change the culture, they introduce the change in their weekly meetings. They can do that because they know every team runs one and every team’s meetings work about the same way. Then, they can adjust how each team runs those meetings to incorporate the new practices.

Defining your team’s MFMs makes it possible to design in your desired culture. You don’t need to rely solely on employee survey data to see if employees feel more innovative or included. You can observe meetings to see if they ask innovative questions, use innovation techniques, and include everyone in the discussion. Building your desired culture into your meeting practice gives you a practical way to drive culture change.

Ok, so those are some of the benefits you get from defining and using Meeting Flow Models in your business.

Next Up

For some of you, this whole concept will feel super obvious. You’re already doing something like this, and we’ve just helped you snap the ideas you already had into place. If that’s you, pull out your “operational cadences” or “communication plans” or whatever you’ve created that’s using similar concepts to see if you can now make them a bit better.

For others, ideas like Communication Architecture, Meeting Design, and Meeting Flow Modelling are all new.

You all are in for a treat, because you’ve been working with collaborative teams in the hardest possible way. You’ve been making it up as you go along, learning from those around you, and trying hard to keep everyone moving forward against an uncharted and stormy sea. When you get collaboration tools like Meeting Flow Models in place, you and your team will finally know how to navigate those waters and keep the wind at your back.

In the next article, we’ll take a look at how to create a Meeting Flow Model.

In the interim, if you’ve got questions or comments on these ideas, we’d love to hear them! Those boxes below are yearning for your input, so please don’t be shy.