Meeting Execution: The Underlying Structure of Meetings that Work

Behind every effort to improve an organization’s meetings, you’ll find a larger initiative focused on increasing productivity and improving culture.

Organizations that run effective meetings as a matter of course do so because it improves the productivity and cohesion of teams as a whole, in a way that individual productivity improvements can’t match.

To maximize the productivity of a meeting, and of meetings in general, it helps to understand exactly what you expect meetings to produce.

Previously, we asserted that meetings should “quickly create shared perspective”.

Let’s unpack that one. What do you get from teams that have a shared perspective?

Shared perspective produces:

- Clarity regarding the work

- What’s done

- What remains

- Who’s doing what

- What problems need to be solved

- Which questions need answers

- The seeds of trust

- When you hear other people’s ideas

- When other people listen to your ideas

- When you learn about the context of other people’s work

- When other people make commitments

- When other people report back on commitments met

- When the agreements you make and commitments you keep are appreciated by others

When a meeting fails to create this shared perspective, it’s usually because the meeting wasn’t structured to do so.

Which is sad, really, because once you understand the basic framework needed for any productive meeting, there’s just no reason to ever spend time in an unproductive meeting again.

The structure, aliveness, deadness, whisper or shout of a meeting teaches and persuades us more about the culture of our workplace than all the speeches about core values and the new culture we are striving for …

What we call meetings are critical cultural passages that create an opportunity for employee engagement or disengagement.

Peter Block, in the foreword to Terms of Engagement: New Ways of Leading and Changing Organizations

So let’s dive into this question of structure.

We’ll look at meeting structure from several angles. Don’t worry! You don’t need to remember all the details.

We’ll explore all these perspectives on meeting structure for the same reason we share ideas in a meeting; because when you look at it all together, it gets easier to see what these frameworks have in common and what really matters.

We Meet to Find the Elephant in the Dark

Specifically:

We meet to quickly create shared perspective in a group.

It can be hard to care about “shared perspective”.

Each person might think he or she knows everything needed to get on with the job, and that this time spent with the group is a waste.

The reality is that we are all working with blindfolds on. There is too much information flowing through the modern workplace for any one of us to fully grasp the “truth” of the matter.

A Parable

This ancient parable illustrates our challenge.

6 people who have never seen nor heard of an elephant enter a dark room. They each touch the elephant hidden inside the dark room to learn about it. Each person feels only one part of the elephant; just the tail, or just the trunk, for example.

Each one forms a true, accurate, and very limited idea of what an elephant is. The person who felt the trunk believes an elephant is like a hose. The person who felt the side thinks the elephant is a wall.

When they compare their ideas, they find they don’t agree at all.

Take a moment to enjoy John Saxton’s version of the tale, put to rhyme.

A properly structured meeting helps teams share, compare, and merge what they know independently into a more complete picture. Together, they can better appreciate the whole elephant.

(Icons from The Noun Project)

Meetings achieve this function by pulling individuals together into a space where they can work to align their disparate viewpoints. Once they’ve assembled a shared perspective on the topic at hand, a successful meeting ensures the group heads out in a unified direction towards that shared goal.

The Essentials of Meeting Structure

Meeting structure is a fancy way of saying the plan for running the meeting.

Structure covers all the how:

- How people will introduce themselves

- How you’ll organize the topics

- How you’ll lead the discussion

- How you’ll review presentations

- How the group will make decisions

- How you’ll capture results

Using the right meeting structure prevents dysfunction and ensures results.

Our agenda template gallery includes many pre-designed structures for running specific meetings. These templates spell out how to prepare for the meeting, any exercises or activities to run during the meeting, and what to write down to make sure the team walks out with a tangible result.

Ultimately, you’ll want to establish that same level of detail for meetings you run often.

That said, every functional business meeting shares a common, underlying structure.

You can think of this underlying structure as a basic outline for a functional meeting. When you understand this core structure, two things become possible.

- You will plan better meetings.

- You will make unplanned meetings better.

Meetings 101: Creating a Mental Model

If there were ever to be college major in effective meetings, coursework would start here.

Why start with structure? Because recent research has debunked the idea that “natural talent” is all you need to excel.

Instead, expertise and mastery come from deliberate practice and having a mental model readily available for tackling the work in front of you.

This post will help you build a basic mental model you can use to structure any meeting.

To understand this basic meeting structure, let’s start way up at the 10k foot level.

From here, we see the basic structure of a meeting and how that meeting fits into the work over time. For each meeting, there is a before, a during, and an after.

Zooming in, we can see the structure of the meeting itself.

Every meeting has a beginning, middle, and an end.

What distinguishes a functional meeting from a waste of time?

In a meeting that works, the team spends more time focused on the beginning and end of the meeting.

Rather than just blips in time, the start and end of meeting are dedicated phases in the process.

The 3 Non-Negotiable Phases of a Meeting That Works

At the most basic, rock-bottom level, a meeting needs these 3 distinct phases.

- Focus and Become Present

- Do the Work

- Wrap It Up

At this minimal functional level, we’re talking about a meeting that isn’t a total waste of time. Teams that go through these three stages will achieve a shared result.

They may not have any fun doing it, but at least they’ll get something out of the time spent.

Here’s what that looks like:

Phase 1: Focus and Become Present

The meeting begins by getting everyone into the conversation at the same time, transitioning them successfully from wherever they were before into the task at hand.

It starts with focus.

A functional meeting must secure the attention of the team before the work can begin. This is why many meetings begin with some form of welcome, roll call, or other activity designed for everyone in the meeting to literally declare themselves “here”.

A focused opening ushers the group into the rest of the meeting, assembling the team together and guiding them into the main show.

People who are multi-tasking, pre-occupied, or otherwise “not really there” cannot participate effectively in creating or understanding the work of the group.

Unfortunately as a meeting leader, you can’t guarantee that the people in your meeting will really “be present” for the discussion. If you fail to clearly open the meeting, however, or to even ask for this presence up front, you greatly increase the likelihood that the meeting will fail.

If you don’t do the work to transition people into the meeting and engage them in the topic, don’t assume they’ll do it on their own.

They won’t.

“Time out!” I hear you cry.

“Work doesn’t happen in meetings! Meetings are where we go to avoid work. Meetings are what keeps us from getting our real work done. I do all my work outside of meetings!”

For you, I have two replies:

- Re-think what you consider work.

Of course tangible production matters – but only if you’re producing something useful, valuable and/or desired. You need to know what to produce, how to do it, by when, with whom, and for whom, and these things often get decided in meetings. If no one does the deciding and coordinating work, your “real” work goes nowhere. - If there is literally no work to be done in a meeting, cancel it.

This is not a guide on how to overthink complicated ways to waste time. It’s about how to structure meetings to make sure they do the work they’re meant to do.

Ok, enough of that. Let’s look at Phase 2.

Phase 2: Do the work

Once everyone becomes present, they can work together to get aligned. When we draw this part of the meeting, it can look a little messy.

Functional meetings result in some tidy outcome: a decision, a plan, a set of action items, a date for the next meeting, and a feeling of time well spent.

The creation of that outcome requires everyone in the group to move from whatever they understood the situation to be beforehand to this new shared understanding. They need to assemble the elephant. There are questions to answer, conflicts to unravel, egos to navigate, and a popcorn smattering of “aha!” moments to enjoy.

People arrive at conclusions at different rates, and as new ideas emerge, the group can get pulled back into the soup. While you can work to tidy up this part of the process, the creation of alignment will always be a bit messy.

Every meeting I’ve ever seen has a “do the work” phase.

Groups always manage to talk about something in a meeting; but they don’t necessarily hear what’s said (because they weren’t really present) or walk away with any noticeable result.

Meetings fail when they only focus on doing the work.

Phase 3: Wrap it Up

That’s why functional meetings always end with a clear review of what the group just created.

Remember, the whole point of a meeting is to ensure the group walks out with a shared perspective.

You can only be sure this worked if you ask.

Before the group leaves, decisions need to be restated, each person must confirm that they understand what just happened, and more importantly, that they know what will happen next as a result.

Many groups who think they achieved their meeting goal skip this step, especially when they’re rushed for time.

Groups that skip this step assume the decision they believe they heard was clear to everyone else. Close perhaps, but unlikely.

And when a group fails to check commitments at the end of a meeting, each person leaves with whatever they felt was most important and heads off in the direction that seems best to them.

Individuals take responsibility for whatever actions they think they own and remember only the details that directly and immediately impact them.

Even if they share the same picture, they may not share the same beliefs about what they’re supposed to do about it.

People often assume that “someone else” will take on any tasks identified in the meeting, then quickly forget most of the discussion.

This can leave your elephant just sitting there in the dark, mucking up the place and waiting to be set free. Not ideal.

From Functional to Successful

So at a minimum, every meeting must start by getting the group really “present” for the discussion before they can work together. Then, once the work is done, the meeting must end by wrapping up to make it clear exactly what’s supposed to happen next.

That’s really a minimum, though. More successful meetings approach these 3 phases with vigor!

Once again, this time with feeling!

Successful meetings:

- Engage!

Go beyond “present” and get the group involved!

(See some tips for leading introductions in business meetings.) - Co-Create

Don’t just do the work and punch the clock – work together to co-create something new! Combine unique ideas and insights to create a shared perspective that’s more complete, more ambitious, and more everything than what any one person could do on their own. - Commit

Don’t just recite a list of outcomes! Commit to acting on the agreements made in the meeting. Every action has an owner, and every owner commits to seeing that action through.

Meetings that end with a new shared perspective and strong commitments to act upon this outcome are not a waste of time.

What if you don’t know why you’re meeting?

This basic structure underlies all well-designed meetings. Unfortunately, to design a really great meeting, you need to know why it’s been scheduled and what it’s meant to achieve, and that’s not always possible.

The good news is that you can use this simple structure to save the day when you’re faced with a meeting that you can’t design ahead of time.

In fact, the default agenda in Lucid Meetings – called the “Basic Agenda” – includes just three agenda items:

- Welcome: where you find out why you’re there

- Discussion: where you do the work

- Review and Next Steps: where you wrap it up

Read more here: The “No clue why we’re meeting!” Agenda

Symptoms of a malformed meeting

What does it look like when a meeting lacks this basic functional structure?

Poor structure is behind many of the common problems you’ll see in a meeting.

Signs of Failure to Focus at the Beginning

Problems you’ll see when there is no opening or “ask” for engagement at the beginning of the meeting:

- People using cell phones or checking email during the meeting

- People who don’t speak up or participate; who aren’t really “there”

- Confusion and false starts, as people try to figure out why they’re there

- Sloppy and/or uncomfortable moments when it’s not clear where the chit-chat ends and business begins

Signs of Failure to Structure the Work

Problems you see when the process for doing the work isn’t clear:

- Rambling discussion; people talk and talk

- Inconclusive discussion

- Running over time

- New topics pop up

- Teams revert to safe answers or give up

- The creation of laundry lists without owners or priorities

Signs of Failure to Wrap Up

Problems you see when the meeting isn’t wrapped up at the end:

- No written communication afterwards

- Only the people in the meeting know what happened

- Nothing much happens afterwards or changes as a result

- Less than 60% of the agreements made in the meeting stick

- You have the same conversation with the same group again later

Any of this look familiar?

Next Level Structures and

The Geometry of Effective Meetings

Now that we’ve covered the basics, let’s build on and strengthen our mental model.

Many experts who help groups run useful meetings have published conceptual frameworks that expand on the 3 basic phases of a meeting.

One of the great blessings of our human wiring is the natural ability to spot patterns, especially when we’re primed for them. If you’ve ever considered buying a car, you may have suddenly noticed that car everywhere you drive. When you’re expecting a child, you start seeing pregnant women and strollers all over the place.

With that in mind, here are four more ways of thinking about meeting structure that reinforce and build on the 3 basic phases outlined above, and an example of how each structural shape maps to a common meeting agenda.

The Diamond of Participatory Decision Making,

a.k.a Diverge, Emerge, Converge

The landmark Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision Making has an unfortunately complicated title for a book that’s actually full of simple diagrams and useful, clear models.

The book’s central conceptual model is The Diamond of Participatory Decision Making. The Diamond illustrates group dynamics, exploring the discussion phases a group will go through as they work to find answers in a meeting.

The Diamond comes in two flavors: simple and complex. The simple version shows what happens when the topic covers known territory and the answers are obvious. It looks like this.

Each small dot in the triangle represents an idea or opinion. The group starts at a unified point, then briefly explores familiar opinions before narrowing in on a decision.

As you can see, the group starts and ends at a focused point. This matches the 3 basic phases discussed above.

The Diamond was designed for facilitators working in large group sessions, and shows what could happen for each major topic in a complex meeting.

That said, for short meetings, standing meetings, and other discussions that have simple outcomes, this simple shape covers the whole meeting.

For example, here’s how a typical 15-minute leadership huddle or agile standup maps to this shape.

Thank goodness not every topic has an obvious conclusion, because how boring would that be?

The second Diamond expands to cover what happens (or – what should happen) when groups work on more complicated subjects.

Here’s the Diamond of Participatory Decision Making in all it’s glory.

As the group realizes that the usual answers won’t do, they begin throwing out new ideas. This is known as divergent thinking; the kind of discussion groups have when they’re making big lists, brainstorming, and exploring “what if?”

After all that mess is out there, it has to get synthesized. Groups begin the hard work of co-creation. This part can be awkward and painful, which is why the authors call this “the Groan Zone”. If they can stick with it, the group will find new ideas that can’t be attributed to any one individual emerge out of the soup.

Finally, the group narrows down the field of possibilities and converges on an answer.

This answer becomes the new shared perspective.

With all those ideas flying around, you can see why it’s so important to end the discussion by wrapping up and confirming exactly what (of all the many possible approaches) the team decided to do. The circles for the start and close may be smaller in this diagram, but they’re no less important.

As an example, here’s how a strategic vision setting meeting maps to the Diamond of Participatory Decision Making.

If that all seemed a bit too abstract, check out this short video from Jeannel King explaining how this works in practice.

Another resource: Gamestorming shows how to chain these diamonds together in longer meetings and workshops designed to cover multiple topics.

The Plot Line

Our second shape comes from the world of drama rather than the world of business meeting facilitation.

Take a look at a standard plot line developed by Gustav Freytag (aka Freytag’s Pyramid).

Freytag developed his 5-part pyramid after studying patterns in Shakespeare and ancient Greek stories, and you can find this structure still clearly grounding much of what’s created today.

Authors continue to use this structure because it works. People know how to follow this kind of story.

A structure everyone can automatically follow and understand is a very desirable quality for meetings too.

CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons

The Evolution of Dramatic Structure

Total – but interesting! – side note:

Freytag’s work built on and extended the dramatic structure that Aristotle introduced in The Poetics.

Aristotle believed in the purity of a simpler 3-part structure, consisting of a “beginning, middle, and end”. Aelius Donatus later formalized these stages as:

- the protasis (introduction),

- epitasis (main action)

- and catastrophe (final resolution).

Sound familiar?

Stories start by setting the scene. The audience gets to know the characters involved, and the context for what’s to follow.

Professional facilitators sometimes refer to the meeting opening as “the setup”, where they’ll introduce the agenda, set the ground rules, and give everyone a chance to introduce themselves and check in personally.

Exposition, or the setup, makes it possible to understand the action that follows.

After that, we get the rising action. This is sometimes drawn with a jaggy line to represent setbacks along the way. In meetings, these are the twists and confusions and random injections that make the conversation more complex.

The rising action leads to a climax – that point in the story where the action comes to a head.

Not every meeting will experience anything we would qualify as a true climax, of course. (These are business meetings after all. Let’s not get too carried away.)

For those that do, though, we can see this happen in those moments where the confusion, disagreement, and uncertainty start to turn into clarity. For example, in the Diamond above, the climax comes as the group emerges from the “groan zone”.

I can’t believe I just wrote that.

During the falling action that comes after the climax, the characters have the clarity they need to start moving forward. Any remaining conflict unravels and decisions get finalized. In a meeting, this is the work getting done.

Resolution and Denouement. In the story, this is the part where our characters clean up after the chaos, and begin getting on with what’s next – eternal remorse, a happy ending, or simply enjoying the lull between sequels.

It’s only at the close of a story that we can process what just happened in the climax, and accept that our heroes have prevailed to fight another day.

In meetings, the wrap-up serves as the the resolution. Closing a meeting well gives everyone involved a chance to process and appreciate the agreements reached.

The story line also gives us a handy timing tip.

There are 5 parts to the plot line: 1 for the setup, 3 for the main action, and 1 to wrap up. Writers are often advised to divide the time spent across these 3 major sections by 15%–70%–15%.

Dividing meetings into 15% for the opening, 70% to do the work, and 15% to wrap up works pretty well too.

For a concrete example of how a meeting might fit along a the traditional plot line, here’s the Urgent Problem Solving Meeting mapped out.

the agenda items in the Urgent Problem Solving Meeting at the bottom

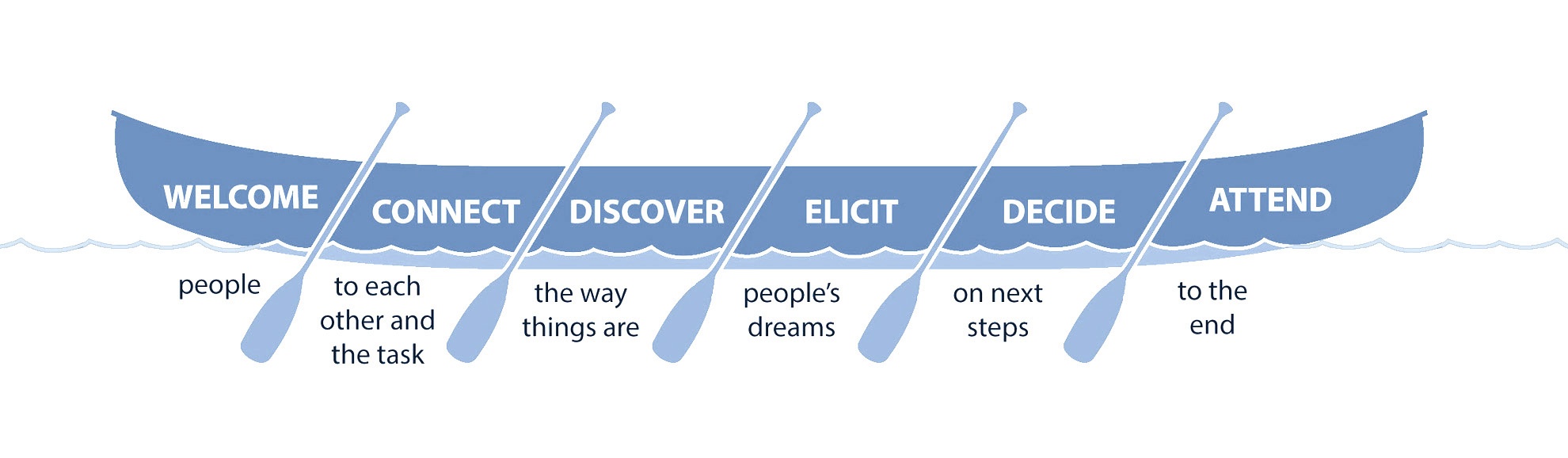

The Meeting Canoe™

One of my personal favorite frameworks comes from Dick and Emily Axelrod, organizational designers and authors of Let’s Stop Meeting Like This. They teach people how to structure meetings using The Meeting Canoe™.

First, let’s get this out of the way. “Canoe” is not an acronym.

The name literally describes the shape of a successful meeting, and how designing meetings that follow this shape will propel a team forward towards a common goal.

As if they were all rowing the same canoe.

The canoe has it’s own description of the phases in a meeting.

Emily and Dick really understand the importance of getting people engaged with each other before diving into the work. The Canoe model dedicates two full oars – “Welcome” and “Connect” – to becoming present.

The next three seats mirror Sam Kaner’s Diamond. Breaking the work into explicit “Discover, Elicit, and Decide” steps is a great way to tidy up what can otherwise be a messy process.

In fact, you can find many drawings of The Canoe™ from above, which boy – doesn’t that look like a diamond?

Personally, I find the “Discover, Elicit, and Decide” explanation a bit easier to use when planning a meeting. Where the concepts of divergent, emergent, and convergent group thinking can help us see how meetings impact group and project dynamics, a reminder to “Discover the way things are” feels a lot easier to translate into an agenda topic.

The last seat on the The Meeting Canoe™ is reserved for the wrap.

Here’s how the 6 sections of The Meeting Canoe™ line up with the 3 basic meeting phases.

And here’s how our most popular meeting design, the Essential Project Kickoff, maps to The Meeting Canoe™.

Of course, there’s a lot more nuance to the Canoe™ than this. This interview with Dick Axelrod, posted by the Singapore Institute for Learning and Organizational Development, describes how to put The Meeting Canoe™ in practice.

(OD here stands for Organizational Designer)

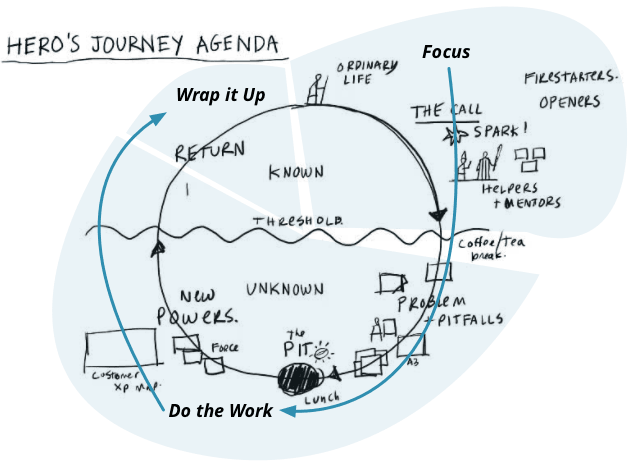

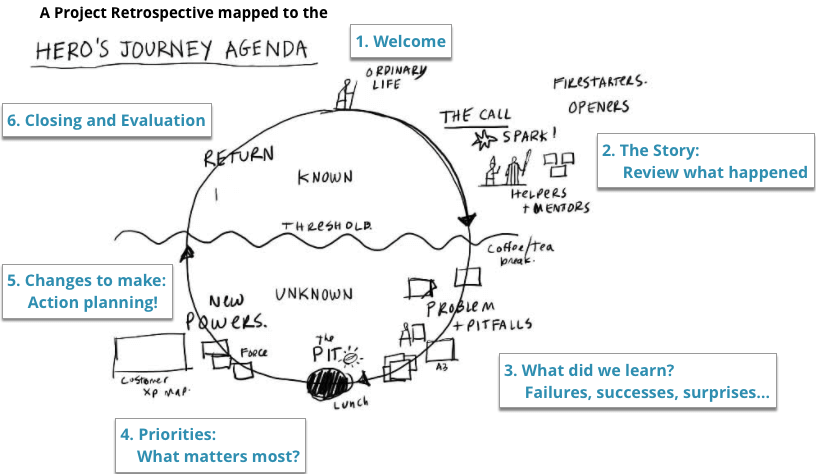

Hero’s agenda

Final shape! Just to mix things up, let’s look at a structure laid out around a circle.

Dave Gray, co-author of Gamestorming, founder of XPlane, BoardThing, and the reigning champion of fun ways to visualize meetings, recently shared his structure for the “Hero’s Agenda”.

To understand how this one works, it’s best to hear it from Dave directly. Click below to see a short video that explains how it works.

Even though this is intended as a model for longer events – workshops, off-sites, and the like – you can still easily see the common structure underneath it all.

And a final example: here’s how our Framework for Successful Project Retrospectives maps to the Hero’s Agenda.

Oversimplifying there, much?

“But hold on!” you say.

“There’s something that doesn’t look quite right in this last map. How exactly is a ‘Review of what happened’ in a project supposed to qualify as ‘The Call‘ that ‘Sparks’ the group into action?”

The answer lies in Meeting Design.

A review doesn’t have to mean sitting around watching someone talk through a slide deck. There are lots of ways to get the facts out there, many of which can be much more satisfying and effective than your standard slideshow snoozer.

The basic structure, as I mentioned in the very beginning, is about ensuring the meeting functions.

Structure is the outline – not the color.

If you want your meetings to be fun, engaging, creative, and maybe even passionate, you’ll need to fill in that structure.

Meeting design is a form of experience design.

Starting with a solid foundational structure, like the ones we’ve explored here, the meeting designer fills in more detail about how the meeting will run and selects a specific process for tackling every topic.

Will you start the meeting with small talk and biscuits, with basic introductions, or with a quick energizing activity? You know you need an opening; meeting design is the process of selecting which kind of opening to use for the meeting at hand.

Wrapping Up

(See what I did there, eh?)

By now, you should have a deep-rooted, down-in-your-belly gut-feel for the structure of a functional meeting.

Getting everyone into a room to “chat and see what happens” does not qualify.

The status update “call-and-respond” drill also doesn’t cut it.

In successful meetings, teams:

- Start by engaging each other, helping everyone become present for the work.

- Do the work to co-create a new shared perspective.

- Confirm decisions and commit to next steps in the wrap up at the end.

And speaking of commitments and next steps:

In our next post, we’ll explore the question of meeting cadence, or how often should your team meet?

We’ll share what the experts recommend, and how the right cadence for your group depends on the kind of work you do (and how fast you want to get it done).

This post is the third in a six-part series exploring what it takes for companies to run consistently worthwhile meetings.

- Introduction: Creating A Foundation for Changing Your Organization’s Meetings

- Meeting Strategy: Why meet? Understanding the Function of Meetings in the Collaborative Workplace

- This post! Meeting Execution: The Underlying Structure of Meetings that Work

- Meeting Cadence: How often should you meet? Selecting the right meeting cadence for your team

- Meeting Design: How to Create Standard Agendas for Your Business

- Meeting Performance Maturity: How to evolve meeting performance across the organization